“Sexually Explicit Holocaust Tale”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

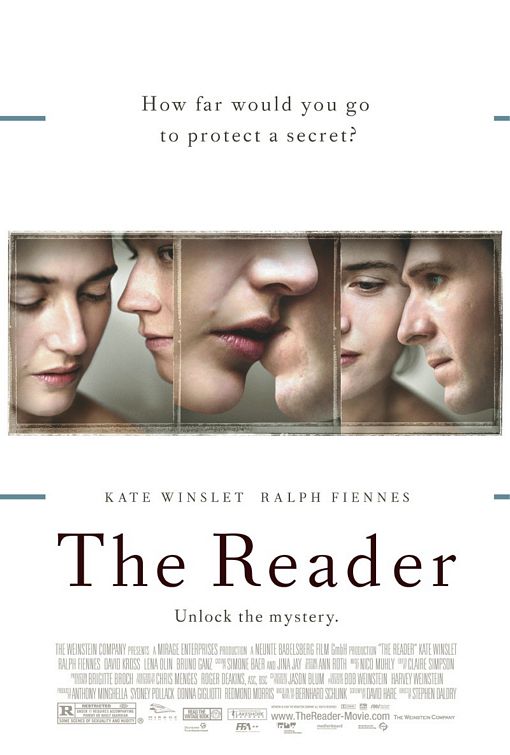

THE READER is well crafted, with strong performances by Kate Winslet and David Kross as the leads. The movie’s first part, however, is clearly pornographic, with very strong sexual content and extensive nudity. Also, the moral worldview in the movie’s second half is too ambiguous and murky at times. Slight changes in the dialogue from the novel’s third act don’t help. Finally, the movie seems to enjoy depicting the sexual relationship between a teenager and a woman more than twice his age. This is just titillating, not enlightening.

Content:

(B, C, PaPa, Ho, L, V, SSS, NNN, A, D, MM) Light moral worldview with light, minor Christian references, but sometimes too morally murky and too morally ambiguous, plus the filmmakers succumb to gratuitous sexual graphicalism wherein a 36-year-old women deliberately seduces a 15-year-old teenager who clearly revels in that seduction, plus an oblique reference to lesbian homosexuality when viewers learn that people falsely wondered whether a woman was some kind of lesbian (which is, however, expressed in a very obscure manner in the movie so it’s not really as salaciously depicted as it may sound); three light obscenities plus an obscene gesture; woman slaps teenager and non-violent references to the Holocaust; very strong sexual content includes multiple scenes of depicted fornication, including seduction and sex scenes where 36-year-old woman has a torrid affair with 15-year-old, plus two brief scenes of young adults fornicating; extreme explicit nudity includes shot of full male teen nudity in one scene, shots of male pubic hair, many shots of upper female nudity, and some shots of rear nudity; brief alcohol use; smoking; and, young man hides important fact at a trial for six Nazi female guards, woman lies at trial to hide a personally embarrassing fact but her lie gets her a really heavy sentence that is arguably unjust (especially since, because of her lie, other people who are arguably more guilty than her get relatively light sentences), teenager lies to his parents to see older woman more than twice his age, and male lead character becomes emotionally repressed and that causes bad things to occur as well as arguably adds a note of psychobabble to the movie’s moral points and character arcs.

More Detail:

The movie opens in flashback with Michael Berg, a 52-year-old lawyer in 1995, thinking about the first love of his life. Jump back to 1958 in Germany, where a sickly 15-year-old Michael is helped back home by a 36-year-old woman, Hanna, played by Kate Winslet of TITANNIC. At home, the doctor orders Michael to bed rest for scarlet fever. Three months later, Michael takes flowers to Hanna to thank her. Hanna catches Michael staring while she’s putting on her stockings, and an embarrassed Michael runs back home.

Michael soon shows back up at Hanna’s apartment. He gets dirty helping her bring up two buckets of coal to her place, and Hanna orders him to take a bath before he goes home. Michael catches Hanna staring at his naked body even though she promised not to do that. At that moment, Michael and Hanna begin a torrid affair, which is explicitly depicted.

Hanna makes Michael read his school literature books to her when he visits, including such things as Homer’s ODYSSEY and Chekov’s story “The Lady with the Little Dog.” Hanna has a job taking tickets on the trolley and gets angry one day when Michael shows up on her trolley. She and Michael have an argument about her feelings toward him. Then, her boss tells Hanna that she’s getting a promotion and will start working in an office. This point will help resolve a major mystery in the movie’s second half.

Hanna suddenly is packing up all her things and leaving the city. When Michael returns to her place, he finds it totally empty.

Jump ahead to 1966. Michael is now in law school. His seminar professor takes the class to a trial for six women who guarded women and girls in a smaller camp. When there was no more room in the small camp, the six women would pick out 60 females and send them to certain death at Auschwitz. Now, one of the young former inmates, who was with her still-alive mother in the camp, has written a book about the smaller camp, which has resulted in the current trial.

Of course, to his chagrin and disgust, Michael learns that Hanna is one of the six Nazi guards. During the trial, however, Michael learns an important fact about Hanna that may have a bearing on her sentence and that of the other defendants. Michael is torn whether to reveal this fact to the authorities.

THE READER is morally complex, perhaps too complex for its own good. As the author of the original novel asks, “If you love someone who is guilty, do you become entangled in their guilt? And, can we choose who we love? It would be simple if the people who commit monstrous crimes were always monsters. But, sometimes they aren’t. Sometimes they are just ordinary people – our neighbors, our lovers, our teachers, and our friends. I had a wonderful teacher who made me love the English language. Later on it came out that he was involved in something truly bad. Can I still like him?” Fleshing out these themes is an excerpt from the novel in the movie’s production notes:

“I wanted simultaneously to understand Hanna’s crime and to condemn it. But, it was too terrible for that. When I tried to understand it, I had the feeling I was failing to condemn it as it must be condemned. When I condemned it as it must be condemned, there was no room for understanding. . .”

These themes and questions sound like valid ones, up to a point, but the movie seems a bit too murky at times. Consequently, at times, fleeting though they may be, a viewer might come away thinking that the movie is making excuses for Hanna’s behavior. At the trial, Hanna withholds an important mitigating fact about herself that’s also personally humiliating for her but not morally humiliating. While watching the trial, Michael figures it out, but decides to honor Hanna’s desire to keep her personal secret. This lets what is arguably a grave injustice to occur. Michael tries to fix things later, but his attempt to make up for it causes a good thing to happen as well as a bad thing to happen.

In the end, the movie does seem to be saying at least two things. The first is that Michael, when he finally meets with Hanna again, is unable to come to terms with his conflicting emotions over Hanna, including his love for her, his disgust over her Nazi past and his sympathy for the personal dilemma Hanna faces during her trial. The movie also seems to be saying that repression of guilt or other emotions and repression of embarrassing, humiliating things are bad. Thus, the final scene shows Michael in 1995 finally telling his adult daughter the story that viewers have just spent two hours experiencing. This second idea sounds a bit like psychobabble, but even here, it’s hard to say what exactly the filmmakers want viewers to get out of this movie. It should be noted, however, that there are some slight, but significant, changes in the dialogue from the novel’s ending, which the movie otherwise follows. The novel also is written from Michael’s viewpoint, which seems to make those scenes more compelling in the book.

It should be noted that the movie sometimes makes Hanna a sympathetic figure, despite the disgust and shock Michael clearly feels about her Nazi past. At the end of the movie, the older Michael has to meet with a Jewish survivor of Hanna’s and the other Nazi guards about some business regarding Hanna. Some of the Jewish woman’s reactions to Michael’s visit come across a bit harsh. Because Hanna is sympathetic at times, especially toward the end, this adds to the moral confusion the movie seems to create. It’s also hard to say whether this problem dilutes the movie’s moral outrage over the events of the Holocaust. On the other hand, while the trial’s occurring, Michael visits the remains of a concentration camp. This sequence clearly focuses the viewer’s attention on the horrors that Hitler’s Third Reich created during World War II and the Holocaust.

The movie’s lack of clarity morally speaking is matched by very strong sex scenes and explicit nudity, which includes a graphic shot of young Michael’s private parts and some shots of his pubic hair. That explicit gratuitous content, along with the fact that the movie unashamedly portrays an adult woman of 36 seducing a 15-year-old teenager, creates a movie that is patently immoral. The explicit sex and nudity add nothing to the movie’s basic story. In fact, it’s fairly pornographic because it’s just titillating, not revelatory, much less enlightening.

- Content:

- Content: