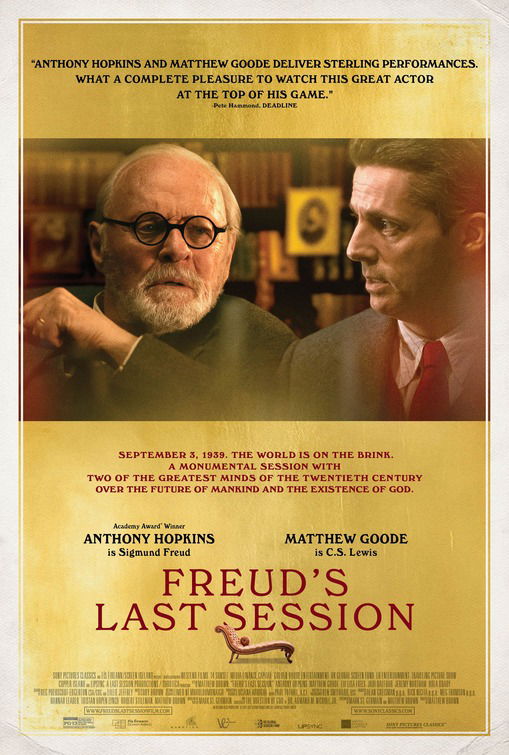

“Faith Vs. Anti-Faith”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

FREUD’S LAST SESSION tells a dramatic and engaging, though talky, story. Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Goode deliver excellent performances as Freud and Lewis, respectively. Lewis gives a hearty defense of God and Christianity from a historical, philosophical, moral perspective. Freud states his case for atheism, sometimes making jokes about the Christian apologist’s faith. In one scene, the movie seems to tip the scales in Freud’s favor when Freud angrily attacks God for the natural deaths a young grandson and a married daughter from disease.

Content:

Movie seems to slightly favor Sigmund Freud’s humanist antagonism toward God and religion in a fictionalized story set in 1938 where Freud meets Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, who strongly defends belief in God and faith in Jesus from a historical, philosophic perspective, but doesn’t give an answer when Freud gets upset about two painful family tragedies where children died of illness, which he says forms his biggest objection to belief in a God (the movie’s Freud character indicates God must either be not all-powerful or not all-good), but both men express opposition to the evils of Hitler’s National Socialist Germany, plus Freud’s daughter Anna has a close female friend, and the movie says they were lesbian lovers (the real Anna, however, denied such a relationship with her close friend);

Two “d” obscenities and four light profanities;

Some flashbacks from World War I, an explosion kills a man’s friend and wounds the man, discussion and radio reports of war developing in Europe because of Hitler’s National Socialist regime in Germany, and one bloody scene shows a man helping another man remove a prosthetic device form his cancer-ridden mouth, plus a postscript says Sigmund Freud took his own life because he was painfully suffering from terminal cancer of the mouth;

There’s a confusing scene with C.S. Lewis kissing and saying goodbye to a woman as he leaves his house to visit Sigmund Freud in his house ;

No nudity;

Brief alcohol use;

Elderly man smokes cigars, and people smoke cigarettes in one or two scenes, but no illegal drugs, though elderly man has terminal cancer and ingests morphine several times for the pain; and,

Atheist gets angry at God in one scene because of one of his daughters and a grandson’s natural deaths and sometimes seems more interested in psychoanalyzing another man than truly listening and considering the other man’s arguments in favor of religious faith.

More Detail:

The movie opens in Freud’s London home on Sept. 3, 1939. Freud’s colleague and protégé Ernest Jones and Freud’s daughter, Anna, had finally convinced Freud in June 1938 to move from Vienna, Australia, which had been taken over by Hitler in March 1938. A year later, Freud is preparing for a meeting with Lewis at Freud’s new home in London while Anna is getting ready to leave for a college lecture she’s doing. By this time, Anna herself had become an important child psychologist, under her famous father’s training. As Anna leaves the house, she greets Lewis, who’s just arriving, saying, “Good luck,” a comment that elicits a puzzled look from Lewis.

After brief pleasantries, Freud has a memory flashback to 1930 in Germany, when he received the Goethe Prize for literature. Lost in the reverie, Freud mumbles a thing or two about that event. Then, when Lewis shows some concern, the debate between their two worldviews begin.

The two men trade insights and bon mots about their different perspectives, with Lewis being the more earnest and serious of the two. At one point, their discussion is interrupted by an air raid drill. In the bomb shelter, Lewis becomes extremely distraught. Flashbacks to his harrowing experience in the trenches during World War I occur, including the death of his close friend, Paddy. Other flashbacks occur about the death of Freud’s father, and about Christian author J.R.R. Tolkien convincing Lewis to study the Bible with an open mind. Also, both men are concerned about what’s happening in Europe, with Hitler German war machine.

Several scenes in the movie deal with Freud’s relationship with his daughter, Anna, who’s following in her father’s footsteps as a psychoanalyst. She’s devoted to her father, but she also has a close female friend, Dorothy. The two women hold hands at one point, and a written epilogue says Anna and Dorothy were lesbian lovers, even though Anna publicly denied she had any such relationship with Dorothy, though she never did marry.

FREUD’S LAST SESSION tells a dramatic, engaging story. The roles of Freud and Lewis are superbly acted by Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Goode as Freud and Lewis, respectively. The Lewis character gives a hearty defense of belief in God and Christianity from a historical, philosophical and moral perspective. The Freud character sometimes makes jokes about it, however, wondering why a man with “supreme intellect” like Lewis should “suddenly abandon truth and embrace an insidious lie.”

In one scene, the movie seems to tip the scales in Freud’s favor when Freud angrily mentions the death of one of his grandsons from tuberculosis and the death of his daughter, Sophie, from the Spanish Flu epidemic after World War I. Lewis doesn’t have an answer right then for Freud about those tragedies. However, earlier in the movie, he had argued, “What if God wants to perfect us through suffering? Make us realize that happiness, real happiness, eternal happiness can only come through Him?” Lewis makes another great argument when he wonders why religions like Christianity make lots of room for science, “but science makes no room for religion.”

FREUD’S LAST SESSION also has some brief references to sex, including Freud’s controversial sexual theories. Lewis argues in favor of marital sex between two committed people and against premarital and extramarital sex. The movie also contains scenes of trench warfare during World War I and a bloody scene where Lewis helps Freud remove a prosthetic from his cancer-ridden mouth.

MOVIEGUIDE® advises extreme caution for the movie’s apparent support of Freud’s atheist argument in FREUD’S LAST SESSION about the cruelty of God letting a child die a seemingly pointless natural death. In the final analysis, the Freud character’s argument is an emotional one, not a logical, scientific argument. In fact, an atheist worldview, or even an agnostic one, has no rational or logical foundation for thinking or feeling that a child’s death, including a particularly horrific one, is morally unjustified. Only a Christian or biblical worldview has a rational, logical foundation for being morally upset about a child’s early natural death from disease. Also, only a Christian worldview offers any comfort at all, moral or otherwise, for human beings in dealing with such a death, because the Christian knows that, despite such dreadful tragedies, Jesus is suffering with them and even helping them in many ways whenever they encounter such tragedies. The Christian worldview also urges people to help other people who are going through such tragedies. And, finally, the Christian worldview also gives us comfort because it tells us that the death, pain, misery, and tears in this world will be washed away in the world to come (Rev. 21:1-4).

- Content:

- Content: