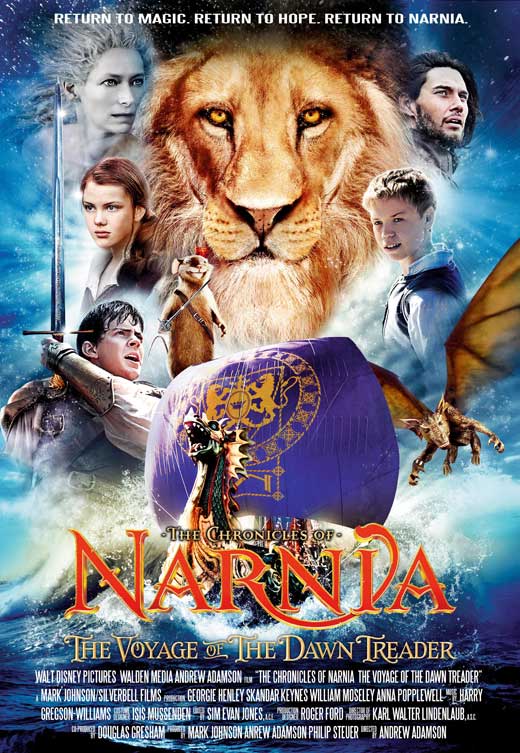

“An Entertaining and Redemptive But Re-Routed Voyage”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

VOYAGE OF THE DAWN TREADER is in every respect a four star movie, in terms of entertainment and production values. Whereas the book is episodic, the movie has a focused goal with a classic story arc. However, the book has been changed in significant ways, and some of the book’s richness has been lost. Even so, the characters are well developed, the dialogue is brisk, the acting is excellent, the special effects are good, and the ending is heart-rending. Though magic is often rebuked, some of it is not, but there are strong redemptive themes, including ones focusing on Aslan’s likeness to Jesus Christ.

Content:

(CCC, O, BBB, VV, M) Strong Christian worldview diminished by magic though the magic is often rebuked, with very strong moral elements, including kindness, compassion, loyalty, real love stressed, and selfishness rebuked, but girl fights in battle against C.S. Lewis’ beliefs; no foul language; strong action violence includes sword battles, attacks by monsters including dragon and sea serpent, people hurt falling, man turned to gold by falling into a lake, boy transformed into dragon and painfully changed back into a human, slaves are roughed up, slaves sent as a sacrifice to the green mist; no sex; fawns and creatures have upper male nudity, but nothing explicit; no alcohol; no smoking; and, green mist preys on people’s sin nature and selfishness.

More Detail:

This episode of the famous third book of the CHRONICLES OF NARNIA opens as Edmund and Lucy Pevensie are staying with their uncle in Cambridge while World War II rages. Peter is off studying for university exams. Susan is on holiday in the United States. Regrettably, their time in Cambridge is greatly challenged by their bratty, selfish, self-righteous cousin, Eustace Clarence Scrubb. Eustace does not have time for any of their Narnia fantasies.

One day, however, while he’s mocking the picture of a Narnia-type ship on a vast ocean, the water from the painting crashes into the room and Lucy, Edmund and Eustace find themselves being rescued by King Caspian in the ocean just in front of the Dawn Treader, the greatest ship in the Narnian navy. Once on board, Eustace cannot stand the gallant mouse, Reepicheep, and they spar both verbally and with swords, with Reepicheep constantly consciously trying to teach the self-centered Eustace a life lesson.

Lucy and Edmund discover that peace has come to Narnia, so Caspian is looking for seven lords who were friends of his father and who went to explore the Eastern sea. Their motivation in the movie is to find the source and thus to stop an approaching ominous green mist.

When the ship lands in Narrowhaven, one of the far islands, they find out slavers have taken over the island, and one of the Narnia lords has been imprisoned. After going through the motions of a slave auction, the slavers seem to reject their economic interests by launching the enslaved people on boats into the ocean to be sacrificed to the evil green mist (none of which is in the book). Caspian and Edmund are sure that the missing residents can be found if the Dawn Treader pursues the quest for the source of the mist. A Narrowhaven resident, whose wife has been sent out to be sacrificed, joins the crew of the Dawn Treader to find his wife. His little girl, Gail, hides on the boat with him.

At their next island stop, they meet the invisible Dufflepuds, who seize Lucy and command her to go into the invisible mansion to read from the Book of Incantations to make all things visible again. Before she reads the appropriate incantation, she reads an incantation to turn herself briefly into her sister, whom she thinks is beautiful. Aslan appears and cautions her not to do this, however.

When things become visible, Lucy meets the wise old magician Coriakin, and the Narnians find out that the Dufflepuds are a bumbling set of bluffers.

Coriakin rolls out a living map where he explains that the Narnains have to make a perilous journey to break an evil spell by finding the seven lords, retrieving their swords and putting them on Aslan’s banquet table. This is the only way to defeat the green mist and the White Witch who exists in Edmund’s memory and symbolizes the evil they face.

The rest of the movie is an exciting race to find the swords so they can go to the edge of Aslan’s land. The last sword is particularly difficult to retrieve. Along the way, Eustace is turned into a dragon and has to repent so that Aslan can strip him of his sin nature.

THE VOYAGE OF THE DAWN TREADER is in every respect a four star movie, in terms of entertainment and production values. Whereas the book is episodic, the movie has a focused goal and a classic story arc. The characters are well developed, the dialogue is brisk, the 3D and special effects are good, and the ending is heart-rending. Georgie Henley as Lucy does a particularly good job of holding the movie together, and Skandar Keynes as Edmund comes into his own as an actor. Will Poulter makes Eustace’s journey come alive. It should be noted, though, that some of the beasts do look more like men in beast costumes than they did in the first two movies.

The movie pursues, as director Michael Apted has noted, two journeys. One is the quest for the seven swords. The other is the characters’ personal growth to reject their sin nature and overcome their temptations.

The importance of belief is stressed, and the object of belief and trust is Aslan. Only Aslan can free Eustace from his dragon nature. Aslan warns Lucy of misusing magic. Aslan appears at critical times to get them through their temptations. And, Aslan makes it clear that he will be with them even in this world – our world, although he goes by another name. Aslan tells them to find His name, which is, of course, Jesus Christ, and get to know Him in our world.

In the process of crafting the movie, the book has been changed significantly. With that, some of the richness of C.S. Lewis’ writing has been lost. Lewis’ ability to write passages with a fanciful sense of humor and delight are replaced by an urgent mission and intensity. This may serve the plot, but, as Walt Disney says, for every tear, you need a laugh, and so a little more of the delightful humor of C.S. Lewis would have helped. Fantasy has been turned much more into legend. The funny sea serpent is now a vicious character. Also, the green mist has been introduced from other books, and the White Witch has been brought back, although she’s not in the book. In the movie, the witch replies to Edmund’s reflection that she was defeated once and for all, by responding to him that she’s still in his memory. Of course, she serves as the face of evil.

Furthermore, although most of the magic is rebuked, some of it is not. For instance, in the scene where Lucy discovers the magician’s Book of Incantations, she is pleased to find a spell that creates snow inside the room.

Director Apted notes, “In the book, the narrative thread revolves around Caspian’s search for the seven lords, but in the film, the quest is for seven swords.” This brings up one of the most important points for Narnia fans. C.S. Lewis writes in such a way that there are layers of meaning in THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA, as explained in the book NARNIA BECKONS. Clothes, for instance, have various different meanings. By putting on the robes in the wardrobe, the children are clothing themselves in effect in their future royal robes. The seven lords, in a way, represent the seven churches of Revelation, as well as the seven deadly, cardinal sins. Some of that symbolism remains so that it is clear that the lord who fell into the dragon lake and turned into gold succumbed to greed, but much of the other symbolism is lost.

Even more important, C.S. Lewis wanted his books to intentionally proclaim a Christian worldview. He saw England, as he says in MERE CHRISTIANITY, as having abandoned Christianity. So, his books are intentionally designed to get people to accept Christ and develop a biblical worldview. One of his last letters (5 March 1961) to an older child, Anne, most fully explains his intentions for the Chronicles of Narnia. Anne seems to have written Lewis about a scene from Chapter XVI, ‘The Healing of Harms,’ in The Silver Chair. Aslan, Eustace and Jill are in Aslan’s Country and they have just witnessed the restoration of the dead King Caspian to full life and youthful vigor. Jill cannot understand what she has just seen, so Aslan explains that Caspian had died and so had he. As C. S. Lewis wrote:

“What Aslan meant when he said he had died is, in one sense plain enough. Read the earlier book in this series called The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and you will find the full story of how he was killed by the White Witch and came to life again. When you have read that, I think you will probably see that there is a deeper meaning behind it. The whole Narnian story is about Christ. That is to say, I asked myself ‘Supposing that there really was a world like Narnia and supposing it had (like our world) gone wrong and supposing Christ wanted to go into that world and save it (as He did ours), what might have happened?’ The stories are my answers. Since Narnia is a world of Talking Beasts, I thought He would become a Talking Beast there, as He became a man here. I pictured Him becoming a lion there because (a) the lion is supposed to be the king of beasts; (b) Christ is called ‘The Lion of Judah’ in the Bible; (c) I’d been having strange dreams about lions when I began writing the work. The whole series works out like this.

“The Magician’s Nephew tells the Creation and how evil entered Narnia.

“The Lion etc. the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

“Prince Caspian restoration of the true religion after corruption.

“The Horse and His Boy the calling and conversion of a heathen.

“The Voyage of the ‘Dawn Treader’ the spiritual life (especially in Reepicheep).

“The Silver Chair the continuing war with the powers of darkness.

“The Last Battle the coming of the Antichrist (the Ape), the end of the world and the Last Judgment.”

The source for this letter is Narnia Beckons and “Bluspels and Flalansferes: A Semantic Nightmare,” in Selected Literary Essays, Walter Hooper, ed. (London: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 426.

In the movie, Aslan can stand alone, or people can link him to Jesus Christ. Thus, Aslan still can be used in the manner that C.S. Lewis wanted.

Most of the greatest writers write on several levels. Shakespeare most often wrote on at least three levels: the spiritual – such as when Hamlet ponders “to be or not to be”; the mundane or material – such as when Hamlet deals with Polonius; and, the fleshly nature – such as when Hamlet deals with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Lewis and Tolkein went way beyond this. Lewis’s work dealt with many levels including a cosmology that brought the spiritual world into the material world, what the Irish like Lewis would call “a thin place.”

When the director says this movie operates on two levels, it ignores the fact that the book operates on a multitude of levels, including the spiritual. This is important.

The church used to look at reality in terms of many different levels, such as: the kerygma or message, which is presented clearly here in this movie; the incarnational, which is the presence of God as manifested in Aslan; and, the sacramental, which is an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace. In other words, regarding the sacramental, when a married person wears a ring, the ring is not the marriage, it is an outward sign of the spiritual condition of being married. This is missing in the movie to a degree, although the filmmakers have done an incredible job of capturing some allegorical and metaphorical Christian meaning.

Today, Christian evangelicals usually focus on the message; Catholics often focus on the sacramental; and, others, such as traditional mainline Protestants, focus on the incarnational – and so, the different groups of the church can barely understand each other. C.S. Lewis understood this and was trying to bring it all together.

For instance, Christianity produced civilization based on chivalry. Chivalry grew from the rules of a Christian monastic order. In that light, women, as Lewis insisted, were not supposed to fight; rather, women were supposed to be protected. For Lewis, this is one important aspect of all of the civilizing aspects of a biblical worldview. In the movie, however, Lucy fights briefly.

In spite of the differences between the book and the movie, the movie should be applauded and commended on its own. It is well made and should be welcomed by the church community. It will certainly be entertaining to those who are not debating the fine points of Lewis or the fine points of theology. Best of all, the magic is usually rebuked. There is a caution, of course, that young children will have to be guided regarding some aspects of the movie, and the violence is scary and intense in some places.

In the final analysis, the filmmakers are to be congratulated.

- Content:

- Content: