“Promote Peace, Compassion and Helping Others”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

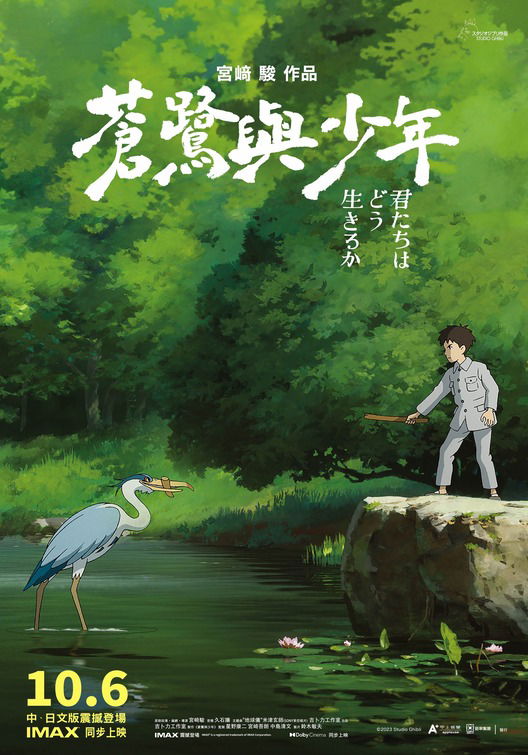

THE BOY AND THE HERON tells a beautifully animated, winsome, sometimes profound story. Though sometimes strange, the story is about birth, life, death, motherhood, and friendship. In the end, it says our purpose is to spread peace, compassion and happiness while helping others. It also has one positive reference to God. That said, THE BOY AND THE HERON has five “d” obscenities. There are also three or so other issues that warrant caution, especially for pre-teen children.

Content:

Strong moral worldview eventually promotes peace, compassion, love, motherhood, helping others, and making the world a better, happier place, plus a character tells the hero, “Godspeed,” at one point, and the hero and his compadres stop a group of menacing giant parakeets and their army from taking over a magical realm, but there is some fantasy magic involving a wizard (the hero decides, however, not to follow the path of the wizard, who happens to be his great, great uncle who went mad from reading too many arcane books), and there’s a reference to the pre-existence of the soul at one point, and the movie’s magical world has a bunch of doors leading to other worlds, implying a multiverse

Five “d” obscenities, and a character tells the hero, “Godspeed”

Some images of violence, fantasy violence and dreamlike violence such as images of a large hospital fire in which the hero’s mother perishes, boy uses a rock to wound his head after being harassed by some bullies to get the bullies in more trouble, a heron bird swipes at a boy’s head, a mass of frogs cover the boy in one scene, some fighting, some old-time sailing ships are said to be ferrying the dead somewhere, giant parakeets menace other characters and form an army, brief fighting, a mass of mean pelicans fly higher to eat a bunch of small oval creatures who are rising in the sky to be born as babies, but the pelicans are stopped, a noble pelican dies because he refused to eat the creatures, a boy is attacked by some strange strips of white paper or linen

No sex, but boy’s father marries his dead wife’s younger sister after the wife dies in a massive Tokyo fire

No nudity

No alcohol use

No smoking or and drugs; and,

Hero frames some bullies and lies about them, but later admits he’s unworthy because of that, another character mixes lies with the truth but admits it, the character also mocks the hero, and giant menacing parakeets intent on

More Detail:

The movie opens in Tokyo during World War II. One night, an 11-year-old boy named Mahito hears that the hospital where his mother works is on fire. Mahito’s father orders him to stay home, but Mahito rushes on foot to the hospital, which is engulfed in flames. His mother clearly doesn’t survive.

Some months later, Mahito’s father moves them to the Gray Heron Mansion, a country estate near a new factory where his father will be working. The factory is building new plastic cockpit hoods for Japanese aircraft in the war. Also, however, Mahito has a new stepmother, Natsuko, who’s also his mother’s younger sister and is now pregnant.

Mahito starts having weird dreams about his mother, who seems to be alive and is calling to him while surrounded by flames. In one of the dreams, his mother rises above the flames of the hospital where she died and asks Mahito to never forget her. Also, a mysterious gray heron seems to take an interest in Mahito, scaring him.

Mahito discovers the mansion was once the home of his mother’s great uncle, who lost his mind from reading too many books and suddenly disappeared. The mansion is staffed by several elderly, comical maids who watch over Mahito.

Mahito starts to explore the estate, led by the mysterious heron, and discovers that there’s another mansion, with a tower, in the woods built by his mother’s great uncle. The mansion, now overgrown by nature, was abandoned when the great uncle disappeared. Strange things occur there, so people avoid it.

At school, some boys, jealous of Mahito’s higher economic status, bully Mahito. Later, Mahito takes a rock and deliberately wounds the right side of his head. He falsely blames the other boys for the injury.

Now bedridden, Mahito seems to have even more strange dreams about his mother. In one of them, his mother, surrounded by flames, is soaring into the air and urging him to come find her.

When Mahito gets well enough to leave his bed, he follows the heron into the woods. The heron reveals himself to be the avian guide of a shapeshifting “heron man.” The heron taunts Mahito and tells him his mother is still alive. About the same time, Mahito sees his stepmother, Natsuko, wander into the woods going toward the abandoned mansion. She disappears in the woods, and his father leads the community and the soldiers staffing his factory to search the woods.

Meanwhile, Mahito and one of the elderly maids follow the strange heron to the abandoned mansion. Mahito follows the heron through a tunnel into the mansion and to a giant library. A voice, presumably the great uncle, commands the shapeshifting heron to be Mahito’s guide. Although the heron objects, he carries out the great uncle’s orders.

Led by the shapeshifting heron, Mahito ventures into a strange magical world, even though the elderly maid disappears at one point. In the new world, dreams and reality blend into one and life and death exist on the same plane. Strange creatures populate the world, including creatures representing the souls of babies about to be born, deadly pelicans who try to eat the soul creatures, and giant parakeets trying to form an army. Mahito also meets a fisherwoman, who appears to be a younger version of another elderly maid, and a young woman named Himi with the power to wield fire.

Mahito wonders if his mother is alive somewhere in this world. Himi and the heron man help him search for his mother. In addition, they must find Mahito’s stepmother and bring her home. They also search for the granduncle, who may have some answers that perhaps can help them.

THE BOY AND THE HERON is beautifully animated and winsome. Although Director and Writer Hayao Miyazaki didn’t lose his mother at an early age, he remembers the bombed-out Japanese cities of World War II. Also, he and his family moved to a more rural area to avoid the bombings.

Like most of Miyazaki’s previous movies, THE BOY AND THE HERON is a fantasy. So, strange, magical events and situations occur. Some of those events and situations are also highly metaphorical or allegorical and sometimes funny, not just bizarre. Overall, the movie tells a captivating, profound story about birth, life, death, creation, motherhood, and friendship.

THE BOY AND THE HERON also has an antiwar theme. For example, the ending clearly promotes the idea of embracing peace, and extols life, compassion and helping make the world a better, happier place. The images of the parakeets gathering and forming to create an army, which are very comical, go along with the movie’s antiwar theme. The gathering of the parakeets also provides a warning to viewers about blindly following the crowd and becoming part of mass movements of people and ideologies, which can do much more harm than good. These are truly, positive messages. Also, at one point, another character wishes Mahito, “Godspeed.” Thus, the movie has one positive reference to God. It should have more than that, of course.

[POSSIBLE SPOILERS] All that said, there are three or so caveats to the acceptance of THE BOY AND THE HERON by media-wise viewers. First, the movie’s explanation about the creatures representing the souls of babies about to be born promotes the heretical idea of the pre-existence of the soul before conception. Second, the character of the granduncle can support the Eastern idea of worshipping ancestors. This one is less of a problem because, in the end, the protagonist decides not to follow the granduncle’s footsteps and take over from him in controlling and improving the magical world created by the granduncle, but to return to Reality and work on improving THAT world. It also turns out that the menacing giant parakeets in the magical world are part of a mistake that the granduncle made while using the magical powers he uncovered in all the books he studied that drove him mad. Third, the movie has a section where Mahito and the other characters can open doors to other worlds. This section implies the idea of a multiverse, which usually is a non-Christian humanist or pagan construct. The idea of a multiverse, especially one that’s limited, can be Christian, or biblical, however, if God, the Uncaused Cause, is the ULTIMATE foundation and creator of such a multiverse. There cannot, of course, be an infinite multiverse, because then God would not be God, and the multiverse would be bigger or just as big as God.

Finally, although THE BOY AND THE HERON creates a fantasy world that’s magical, where the granduncle has access to magical powers, eventually, the hero, Mahito, rejects the use of magic. Also, he leaves the magical world where his granduncle wields magical powers to return to the real world to make THAT world a better, happier place.

Regarding THE BOY AND THE HERON, MOVIEGUIDE® advises caution for older children. However, on the whole, it’s a fun, clever, winsome, and often funny fantasy that’s relatively family friendly. There are, however, some weird, scary moments and five “d” obscenities. MOVIEGUIDE® saw the Japanese version, but there is a dubbed English language version starring Christian Bale, Dave Bautista, Willem Dafoe, Mark Hamill, Robert Pattinson, Florence Pugh, and Luca Padovan as Mahito.

- Content:

- Content: