| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

Content:

Mild moral worldview with some mild feminist elements & a mild critique of capitalism that may cover a much stronger Marxist & humanist worldview, plus some hedonistic/pagan behaviors & an important mild Christian prayer vigil that seems to save a person’s life; 20 obscenities & 6 profanities plus woman gives lewd gesture to man; moderate sexual violence by man against woman, woman slaps man, woman pulls rival’s hair, two friends slap & shove each other during argument until one threatens to kill the other, & suicide by jumping out two-three story window; two scenes of implied fornication, one scene of depicted fornication, another couple shown in bed after fornication, & mild discussion of sex, but most of movie pretty tame; upper male & female nudity several times, rear nudity once, & obscured frontal male & female nudity shown once; alcohol use; smoking; and, lying, woman shoplifts jacket and woman eventually rejects fat bouncer for rich, abusive, promiscuous man.

More Detail:

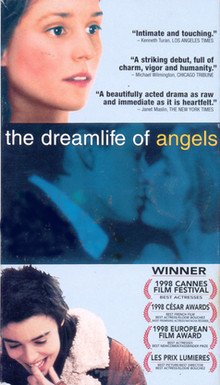

THE DREAM LIFE OF ANGELS, a 1998 French movie recently released in the United States, follows these patterns. It tells the story of how the close friendship between two young women unravels when one of the women follows a destructive lifestyle which includes sleeping with a rich young owner of a nightclub who obviously cares little about her.

Isabelle and Marie, played by Elodie Bouchez and Natacha Regnier, respectively, become roommates when Marie allows Isabelle (Isa for short) to stay with her. The two women barely make ends meet, but they can afford a nice apartment because it belongs to a mother and daughter who are in a deep coma from a traffic accident. Marie’s aunt helped Marie get the house-sitting gig.

Marie briefly takes up a sexual affair with Charlie, the chubby bouncer of a nightclub called The Blue. She abandons Charlie, however, for Chris, the rich, skinny owner of the nightclub. Although Marie at first fights off the advances of Chris and reluctantly and dispassionately lets him make love to her, she develops strong feelings for Chris, even when she secretly finds him kissing another blonde in the nightclub. Isa keeps warning Marie about Chris, but she never listens and the two friends, who have grown close, begin to argue.

Meanwhile, Isa starts reading the diary of Sandrine, the comatose daughter of the owner of the apartment. She develops an affinity for this other young woman and decides to visit her in the hospital, where she learns that the mother has died. Her sympathy for the comatose Sandrine grows, and Isa starts writing in the diary herself.

The rest of the movie resolves the questions of what will become of Isa and Marie’s friendship, what will become of Marie’s affair with Chris and will Marie’s kindness help Sandrine snap out of her coma? The French stars and the filmmakers carry out this story in a moving, intelligent way that ends in one tragedy and two somewhat happy endings.

First-time feature director Erick Zonca, who also co-wrote the screenplay for this movie, makes the audience care about these characters. Despite some extreme foul language, sex and nudity, his worldview seems mildly moral. He even includes a silent prayer vigil by Isa near the hospital chapel when Sandrine suddenly takes a turn for the worse. No words are spoken during the vigil but the milieu is Christian because the audience sees an old man give the sign of the cross in these brief scenes.

There is, however, a mild element of feminism and anti-capitalism in the movie, because Marie and Isa are struggling to survive in a harsh world where good jobs are scarce and businessmen are mean. Both these women deserve a better life, the movie seems to be saying, even though no socialist or Communist solutions are offered. In the end, Isa’s moral courage and compassion stand out strongly in the movie, but the final scene leaves it an open question whether society’s harsh realities will eventually snuff out her courage and compassion completely. It is that open ending which finally puts THE DREAM LIFE OF ANGELS in the fine tradition of foreign art movies, rather than the equally fine tradition of classic Hollywood cinema.