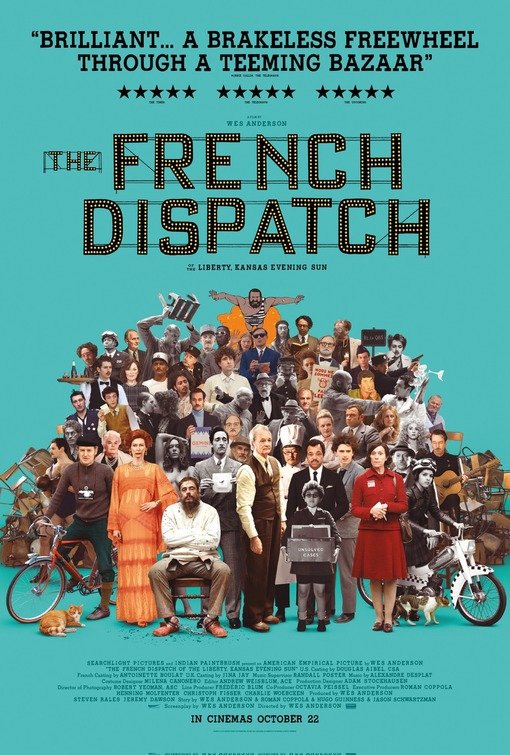

“Marred by Excessive Nudity, Political Correctness and Obscenities”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

THE FRENCH DISPATCH is meticulously crafted. It’s elaborately designed, with multiple references to French culture and real-life writers and articles. THE FRENCH DISPATCH is funny and sometimes touching in quirky, winsome ways. The fourth story contains some exciting moments. However, THE FRENCH DISPATCH is marred by extreme nudity in one story, a few “f” words and political correctness, including brief homosexual references.

Content:

Mixed pagan worldview with a comical, satirical tone seems to lack a religious, moral perspective overall but has some moral elements especially when police and some residents act to rescue kidnapped boy, a comment is made that choir boys are drunk on Christ’s blood after church and harass a homeless old man, some strong politically correct content includes communist elements against imperialism and society and Romantic comments about society oppressing or looking askance at homosexual people when a man is arrested for being in a homosexual saloon

11 obscenities (a few “f” words and a couple “h” and “s” words, including the French word for “s”) and one “Good God” profanity

Light and strong violence includes criminals kidnap young boy and tie him up in a closet, criminals and police exchange gunfire in two or so scenes, criminals are poisoned to death to save kidnapped boy, police burst through two walls of a building and point their guns every which way, an animated sequence shows the police chasing man driving the young kidnap victim in a getaway car, police fire some bullets at the fleeing vehicle, painter in a wheelchair (he hurt his leg) chases art dealer, and art dealer hurls a plate at him, rioting prisoners burst through a prison wall toward a bunch of people holding an art showing in the prison, and the action freezes as a narrator reports that about 10 people died but one character saved people and was rewarded, police shoot tear gas at a student protest, and character climbs atop a radio tower in a thunderstorm to fix it, and it’s later reported the tower fell, and the character was killed

Implied fornication and painter touches nude models bare stomach with his brush and finger but she eventually slaps him away

10 or more separate images of total frontal female nudity, about three images of just upper female nudity, at least one image of just rear female nudity, and upper male nudity as a young man and his middle-aged lover in pajamas sit up together in a bed

Some alcohol use

Some smoking and light reference to criminal syndicate selling drugs; and,

Kidnapping of young boy, boy is held hostage.

More Detail:

Bill Murray plays Arthur Howitzer, Jr., the elderly American editor of the magazine and provides the connecting link to between the stories. Years ago, Arthur convinced his wealthy newspaper family, which runs the Evening Standard in Liberty, Kansas, to let him go to France and start a special magazine insert for the newspaper. He loves working with the writers, though he sometimes haggles with them over expenses.

Each of the four stories in the movie are narrated by the writer.

The first story stars Owen Wilson as a travel writer who gives a bicycle tour of the town of Ennui-sur-Blasé, including the rats who’ve built a large domicile next to the underground subway. When he finishes his tour, Arthur asks him if he couldn’t make his article a little less seedy, but the writer refuses.

The next story involves a painter named Moses who’s also an inmate in the local insane asylum for murdering two bartenders. After serving 10 years of a 50-year sentence, Moses decides to take up basket weaving before he becomes so bored and depressed that he commits suicide. Moses decides basket weaving is too simple minded for him, so he asks the female guard, Simone, for some paints, canvas, brushes, and turpentine. Simone begins an affair with the scruffy-looking, bearded Moses, who soon convinces her to pose fully nude for him. The resulting abstract painting attracts the attention of an art dealer named Julian, who convinces his two uncles to help him buy the painting for their business. Julian anxiously awaits Moses’ next painting, but he’s in for the surprise of his life.

The magazine’s middle-aged social writer, Lucinda, narrates the third story. Lucinda begins covering a student protest movement at the local college. Led by an emaciated young man named Zeffirelli living with his parents, the students want coed dorms so that the males can be with the females. Lucinda loses her journalist objectivity and starts editing the manifesto Zeffirelli is writing. Soon they are sleeping together, though the boy is also sleeping with one of the female protest leaders, a hard-nosed young woman named Juliette. Eventually, the student protest becomes more political when one of their fellow students returns from war and refuses to go back.

In the fourth story, a black homosexual writer is assigned to attend a fancy dinner prepared by the renowned police cook of the city’s police commissioner. The story becomes an exciting, nail-biting thriller when some thugs kidnap the Commissioner’s young son, Gigi, who has a knack for solving crimes like his father. They threaten to kill Gigi unless the Commissioner releases the local crime syndicate’s accountant, who was recently arrested.

The movie ends with all the magazine’s writers sitting around the offices writing the obituary for Arthur, who suddenly died of a heart attack. It becomes clear they loved the man because of his kindness, encouragement and professional support.

Writer/Director Wes Anderson (ISLE OF DOGS and THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL) dedicates THE FRENCH DISPATCH to about 10 famous writers of yesteryear whose work has appeared in The New Yorker magazine. Anderson says the movie is inspired by his love for the New Yorker, the kind of writers the magazine publishes and his love for French cinema. The movie is set in France, where Anderson has spent most of the last 20 years, but in a fictional city representative of the country.

THE FRENCH DISPATCH is meticulously crafted. As usual with a Wes Anderson movie, the sets and lines of dialogue are elaborately designed and written. There are multiple references to French culture, French movies and real-life writers and articles. Parts of some scenes are shot in black and white, which shifts to color photography at crucial moments.

The movie’s droll humor and satirical comedy won’t appeal to everyone, but the movie has so many comical moments that laughter comes easily. The movie also contains some touching, exciting moments. Anderson gets excellent performances from his cast, but the performances are sometimes designed to come across as a little stilted or unemotional. Anderson seems to prefer more nuanced performances, not highly emotional ones. The best stories are the first and the fourth one, though the second one has some unexpected surprises.

That said, THE FRENCH DISPATCH is marred by strong objectionable content. For example, the story about the painter in the insane asylum contains full frontal nudity when the man starts painting his female guard, who’s totally naked in multiple shots. The movie also has some strong obscenities, including a few “f” words. Finally, THE FRENCH DISPATCH contains some Marxist political correctness, including references to the homosexuality of the black writer, who’s partially patterned after the famous black communist homosexual writer James Baldwin. The black writer in the story isn’t as political as Baldwin, but his character is clearly an homage to the erudite personality that Baldwin often projected. Eliminating the extreme nudity and unnecessary foul language would make THE FRENCH DISPATCH much less objectionable. The movie’s worldview is rather ambiguous and mixed. It seems to lack a moral, religious perspective except in the sequence where the police and some residents act to rescue a kidnapped boy.

- Content:

- Content: