| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

Content:

Pagan worldview of older man romancing much younger woman; 28 obscenities & 6 profanities; depicted fornication; upper female nudity; alcohol abuse, and, lying.

More Detail:

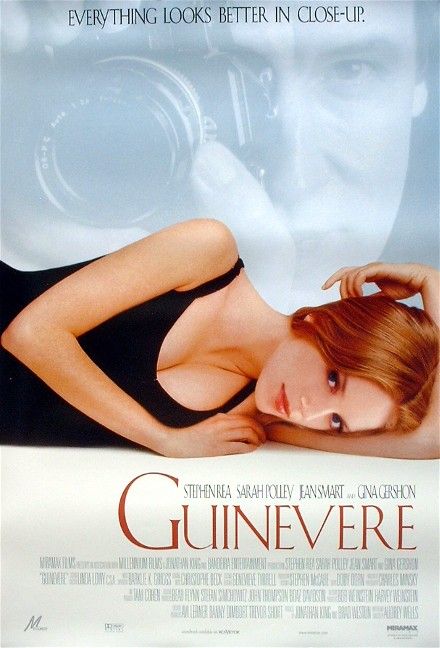

GUINEVERE is a re-telling of the age-old story between a young, naive woman and an older man. Hollywood has done that recently with SIX DAYS, SEVEN NIGHTS, SABRINA and ENTRAPMENT. Few tell the bitter truth about such drastic differences, but GUINEVERE attempts to do so. While the acting and production values are high, the story is slow, and the moral is less than satisfying.

GUINEVERE falters in its inability to make a statement. It’s almost as if the filmmaker refused to take a stand and so the audience watches the painful and sometimes slow romance unfold, knowing how it’s going to end. GUINEVERE, as a story, seems to say that it doesn’t matter if someone throws away an Ivy League education to have a sexual fling with an older man, if at least she had a good time. Guinevere, a.k.a. Harper Sloane, (Sarah Polley) herself says of the affair, four years later, that “He (Connie) was the worst man I ever met – or maybe the best. If you’re supposed to learn from your mistakes, then he was the best mistake I ever made.”

Harper Sloane, a 20-year old woman who is spending her summer waiting for the Fall season where she will attend Harvard. She meets Connie Fitzpatrick (Stephen Rea), a 50-somehting photographer who tells her how beautiful and talented she is, and she’s smitten. The audience’s sees why. Harper’s upper class San Francisco family is cold and harsh. Dinnertime is an ordeal of one-upmanship that speaks of years of bitterness and hatred.

The audience is supposed to applaud the fact that Harper lies to her family to move in with Connie. Even after she finds out that Connie has referred to several other young woman as his “Guinevere” and even used the same lines of seduction, Harper falls back into his arms. In her first night at his place, he says, “There’s lots of reading matter here,” he says. The book on top of the stack is the photography of Alfred Steiglitz. It falls open to a page. “That’s Georgia O’Keefe,” she says. He tells her, “When they met, he was a famous photographer, and she was about your age.” His intentions are obvious, but Harper who must be somewhat bright, doesn’t care.

Besides the obvious problem of morality, the other problem is this may be subject matter for a novel. It’s not for a two-hour film. The audience waits and waits for the inevitable light bulb to go in Harper’s head: that this is an old man who is using her to try to feel good about himself.

Harper comes from an upper class family of cold wealth. Her mother played with power by Jean Smart sums the affair by asking, “what do you see in girls her age that you don’t find in women my age?” Slowly, Connie reveals his alcoholism and distaste for work. He becomes pitiful. He lies to himself and to Harper saying he will bring out the “artist” in her. This never happens with Harper, although it does with others whom the audience later meets in the movie. Because this is an age which applauds non-judgement to celebrate the “best mistake,” Harper ever made. Why? It is unclear what she gains from her time with a 50-year-old lothario.

While GUINEVERE fails as a movie, Sarah Polley, who startled the film watching community with her tender and frightening performance in THE SWEET HEREAFTER gives a wonderful performance. Stephen Rea has a one-note role which he fills well. Yet, Jean Smart steals the movie her scene in the loft where she sums it all up.

Hollywood has loved to pair older men with younger women, without any examination of its actual meaning and ramifications. This ageism, however, didn’t pass Audrey Wells who wanted to demonstrate that this type of coupling often has its bitter rewards. Though effective and valid in its purpose, the execution and conclusion leave only shadows of what true love could be.

GUINEVERE falters in its inability to make a statement. It’s almost as if the filmmaker refused to take a stand and so the audience watches the painful and sometimes slow romance unfold, knowing how it’s going to end. GUINEVERE, as a story, seems to say that it doesn’t matter if someone throws away an Ivy League education to have a sexual fling with an older man, if at least she had a good time. Guinevere, a.k.a. Harper Sloane, (Sarah Polley) herself says of the affair, four years later, that “He (Connie) was the worst man I ever met – or maybe the best. If you’re supposed to learn from your mistakes, then he was the best mistake I ever made.”

Harper Sloane, a 20-year old woman who is spending her summer waiting for the Fall season where she will attend Harvard. She meets Connie Fitzpatrick (Stephen Rea), a 50-somehting photographer who tells her how beautiful and talented she is, and she’s smitten. The audience’s sees why. Harper’s upper class San Francisco family is cold and harsh. Dinnertime is an ordeal of one-upmanship that speaks of years of bitterness and hatred.

The audience is supposed to applaud the fact that Harper lies to her family to move in with Connie. Even after she finds out that Connie has referred to several other young woman as his “Guinevere” and even used the same lines of seduction, Harper falls back into his arms. In her first night at his place, he says, “There’s lots of reading matter here,” he says. The book on top of the stack is the photography of Alfred Steiglitz. It falls open to a page. “That’s Georgia O’Keefe,” she says. He tells her, “When they met, he was a famous photographer, and she was about your age.” His intentions are obvious, but Harper who must be somewhat bright, doesn’t care.

Besides the obvious problem of morality, the other problem is this may be subject matter for a novel. It’s not for a two-hour film. The audience waits and waits for the inevitable light bulb to go in Harper’s head: that this is an old man who is using her to try to feel good about himself.

Harper comes from an upper class family of cold wealth. Her mother played with power by Jean Smart sums the affair by asking, “what do you see in girls her age that you don’t find in women my age?” Slowly, Connie reveals his alcoholism and distaste for work. He becomes pitiful. He lies to himself and to Harper saying he will bring out the “artist” in her. This never happens with Harper, although it does with others whom the audience later meets in the movie. Because this is an age which applauds non-judgement to celebrate the “best mistake,” Harper ever made. Why? It is unclear what she gains from her time with a 50-year-old lothario.

While GUINEVERE fails as a movie, Sarah Polley, who startled the film watching community with her tender and frightening performance in THE SWEET HEREAFTER gives a wonderful performance. Stephen Rea has a one-note role which he fills well. Yet, Jean Smart steals the movie her scene in the loft where she sums it all up.

Hollywood has loved to pair older men with younger women, without any examination of its actual meaning and ramifications. This ageism, however, didn’t pass Audrey Wells who wanted to demonstrate that this type of coupling often has its bitter rewards. Though effective and valid in its purpose, the execution and conclusion leave only shadows of what true love could be.

- Content:

- Content: