“Flawed Expressions”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

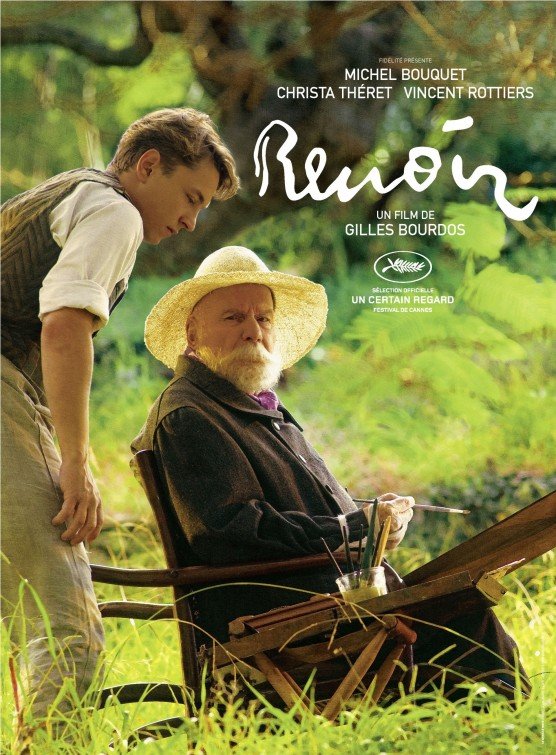

RENOIR is sumptuously photographed. It seems fairly accurate in its depiction of both the famous father and the famous son, as well as the son’s girlfriend, who later will become his first wife. The woman will also star in the son’s first silent movies. However, there’s an abundant number of explicit nude scenes in RENOIR. This, and some false notions about art and life, make RENOIR unacceptable viewing. RENOIR does have some positive moral and patriotic elements, however.

Content:

(RoRo, RHRH, B, P, Ho, LL, VV, S, NNN, A, D, MM) Strong Romantic, immoral worldview seeing art more as personal self-expression, even to the point of being crass, rather than as a way to honor God and God’s Creation, which in turn seems to distort a famous painter’s apparent philosophy of art in a revisionist history way, mitigated slightly by some moral, patriotic elements, plus some brief homosexual and cross-dressing allusions when man searches an avant-garde nightclub for his girlfriend, who’s upset with him because he’s decided to return to battle during World War I; 25 obscenities; no depicted violence, but some strong visual depictions of war wounds, including a couple bloody ones, plus some people struggling in one scene and elderly man suffers terribly from arthritis in his hands; implied fornication, brief homosexual and cross-dressing allusions in one scene at an avant-garde nightclub, and young woman poses nude for elderly painter who clearly admires her naked body but nothing happens between them; extreme nudity in one or two scenes involving full frontal female nudity and lots of shots of upper and rear female nudity, especially upper, plus some upper male nudity; alcohol use; smoking; and, strong miscellaneous immorality includes immoral bohemian lifestyles, painter expresses a somewhat hedonistic attitude about art in one scene, and another man proposes taking financial advantage of the families whose sons have died in battle and been buried in mass graves, which angers one of the two lead male characters.

More Detail:

The movie begins in 1915 with the young woman, Andrée (as a stage and movie actress, she later changed her name to Catherine), riding on her bicycle to begin posing for the father, Pierre-Auguste, at his villa on the French Riviera. Andrée meets Renoir’s youngest son, Claude, and begins posing for Renoir. She soon learns that both Renoir’s other sons, the oldest one named Pierre and the middle one named Jean, have been wounded, Pierre in the arm and Jean in the leg.

One day, Jean comes home on crutches to convalesce. Like his father, Jean immediately becomes intrigued by Andrée, and the two begin an affair. A crisis between them eventually occurs when Jean decides he wants to become a pilot in the war. His decision also causes friction with his father.

RENOIR is sumptuously photographed. Happily, it shows Jean Renoir’s budding fascination with the movies, which is spurred on by Andrée or Catherine, who later became Jean’s first wife. (In fact, Jean claimed that he first became a filmmaker to make his wife a famous movie actress, but the two separated in 1931.) Jean Renoir later went on to make such classic, acclaimed French movies as GRAND ILLUSION and RULES OF THE GAME, often named as two of the very best movies ever made. RENOIR also shows the painful process Jean’s father, wracked by arthritis, had to go through during his elderly years as a painter.

However, RENOIR often shows the famous painter painting nudes. This part of the movie is somewhat exaggerated, as there are also some paintings of Jean’s future wife with her clothes on, rather than off, her body. It also has a Romantic view of art overall, where art is considered more as a means of self-expression rather than something to honor God and God’s Creation. For example, in this movie, Pierre-Auguste at one point says he sees his artistic calling in a rather crass way, to celebrate “flesh,” especially the naked flesh of women (in one funny scene, the model says that Renoir always seems to paint her with more fat than she actually has). This Romantic, immoral attitude in the movie is mitigated by the attitude of his son, Jean, who has a rather patriotic concern for his country as well as a moral concern for the ravages of war. In the end, Jean can’t stand to see his brother soldiers continue to take on the burden of war. Neither can he sit idly by having fun with his girlfriend, Andrée, while his brothers face the ravages of war. Jean’s father finally reconciles himself to his son’s conviction, and the two part warmly when the time comes for Jean to return to the war. Even Andrée, Jean’s girlfriend and his father’s favorite model in the last years of his life, makes peace with Jean’s decision.

Thus, RENOIR ends on an uplifting note, though the rest of it goes a bit overboard, especially in the nudity department.

RENOIR also seems to distort Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s philosophy of art. The movie rightly suggests that Renoir was concerned about bringing happiness to people, not despair. According to Lawrence Hanson in his 1968 biography of Renoir (http://www.adherents.com/people/pr/PierreAuguste_Renoir.html), Renoir was a Catholic and thought that the kind of realism preached by such artists as the famous French “realistic” novelist Emile Zola was “sadistic.” Thus, he didn’t want to paint about the harsh realities of people’s lives, but to paint about the things they did to play, have fun, and enjoy life. Hanson adds (RENOIR, Dodd, Mead & Company: New York (1968), page 157):

“The French have always been realists. They were realists then. To be realistic, they thought, was to earn one’s living then forget about it as quickly as possible; if they were paid little, drinks, food, dances, theatres, circuses cost little too. They were expected to put a happy face forward, and as it was in their own interest to do so, and as it is nicer to smile than to frown, and just as easy, they concentrated on the smile.”

This information about the real Renoir seems to contradict the movie’s version of the painter in the brief crass dialogue mentioned above. In effect, the movie’s version in this one scene can be accused of giving a somewhat simplistic reading of Renoir’s philosophy. In real life, he claimed to be a Christian believer who wanted “to spread joy through his painting” (Hanson, 280). In doing so, his paintings depict happy people who almost melt into the vibrant colors of their surroundings, including their clothes (if they wore them). Giving people joy in your art can almost be seen like a dictum of God’s Law. After all, life is tough enough without always focusing on the despair, hopelessness, and harsh realities of life. To bring joy to someone through one’s art, therefore, can be like a healing touch from God.

There’s an aspect of this in the son, Jean Renoir’s, movies, despite moments in them where harsh realities do indeed come to the fore to hit the characters in the stomach. In the end, however, despite the deep sadness that sometimes seeps into Jean’s movies, there are also transcendent moments of hope. None of these moments is more hopeful, perhaps, than the ending of GRAND ILLUSION, where the two French prisoners of war barely escape to freedom in the snowy mountains of Switzerland. German soldiers raise their guns to shoot them, but suddenly put down their weapons when they see they’ve crossed the border. Movies with tragic endings can be very powerful and insightful, but movies with happy endings are to be treasured.

One final interesting point about the movie. It insightfully hints that World War I not only had a significant impact on Europe and Russia (not to mention America) but also on Jean Renoir. The same thing appears to have occurred in the careers of Christian authors J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. This leads one to ponder, with more than a little awe: What would the work of these men have been like without that experience?