“The Cost of Freedom”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

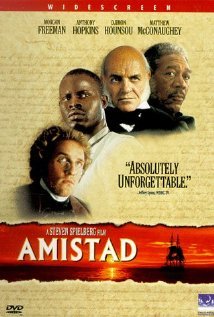

Director Steven Spielberg handles this morally positive story with his usual flair and includes a powerful depiction of the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. The Christ story gives hope and comfort to two of the embattled Africans. Viewers should be warned, however, that although the film also contains no obscenities or profanities, it does include glimpses of female and male nudity, some terrible violence and a minor but diluted reference to ancestor worship. On the other hand, AMISTAD contains a rare historical balance, something which many Hollywood films seldom give us. AMISTAD is an excellent and quietly powerful movie

Content:

(BB, CC, P, Pa, NN, VVV). Moral worldview with strong Christian elements including a positive depiction in one of the film’s major climaxes of the life, death, resurrection, & ascension of Jesus Christ plus a patriotic speech on the Founding Fathers & Liberty at the end of the movie & regrettably including some references to paganism & ancestor worship which is abhorrent to God; no foul language; naturalistic nudity including male & female nudity; extensive violence during scenes on slave ships, e.g., one group of African men & women is deliberately & graphically drowned, two African men are brutally whipped, slave traders beat men, women & children into confined space, plus brutal fight between Africans & slave traders where one slave-trading Spaniard’s throat is cut, another Spaniard has sword thrust through his belly & several Africans are stabbed, shot or punched.

More Detail:

AMISTAD tells the true story of a group of Africans, who in 1839 revolt against the masters of a Spanish slave ship, La Amistad (Spanish for Friendship), but are imprisoned in Connecticut after being captured by the U.S. Navy. The movie opens with a marvelous shot of the Africans’ leader Cinque (Djimon Hounsou) struggling ferociously in the dark to break his chains during a terrible storm, flashes of lightning illuminating the sweat on his face. With terrific rage, Cinque and his fellow captives kill all but two Spanish slave traders on the ship and demand that they sail back to Africa. The two slave traders, however, trick the Africans into sailing to the United States of America, where they are captured and imprisoned in New Haven, Connecticut. Cinque and the other Africans are put on trial for murder. The two Spaniards meanwhile want their “property” back. The Queen of Spain petitions U.S. President Martin Van Buren to extradite the Africans, and the Navy officers who picked up the Africans claim them as salvage.

Into this legal morass step two abolitionists, the white abolitionist leader Lewis Tappan and ex-slave Theodore Joadson (Morgan Freeman), one of the few fictionalized characters in the movie. Joadson and Tappan enlist the aid of lawyer Roger Baldwin (Matthew McConaughey). Through brilliant legal maneuvers, Baldwin convinces the two abolitionists that the case is really not a property case because Cinque and his fellow Africans were not born into slavery but were forcibly kidnapped. Therefore, they legitimately rebelled against their captors and should be returned to Africa. Baldwin is set to win the initial trial but President Van Buren is up for re-election and needs to win the Southern vote, so he uses his power to prevent a jury trial and causes the case to be tried before a different judge, a much younger man with a future legal career to protect.

At this point, Baldwin and the abolitionists seek the help of former President John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins) who is now an unpopular, cantankerous representative in the U.S. Congress. Adams, the son of John Adams, America’s second president after George Washington, is also an opponent of slavery, though he refuses to be identified with the radical abolitionist movement. He advises Baldwin that the court needs to know not just from what part of Africa Cinque and the other Africans come but who they are and what their story is. Baldwin thus finds another black man who can translate the language of Cinque, whom the Africans consider their leader because he once killed a lion with only a rock. A major part of the film concerns Baldwin’s growing friendship with Cinque and his discovery of Cinque’s tragic past. Eventually, the case reaches the U.S. Supreme Court, where Adams uses his own relationship with Cinque to deliver the closing argument.

AMISTAD presents a moral worldview through most of its running time. Viewers should be warned, however, that the slave rebellion opening the film contains two bloody, brutal deaths. Also, the movie contains nightmarish scenes aboard a Portuguese slave ship, including upper female nudity, incidental shots of male private parts and a horrible scene where Africans aboard the ship are drowned by chaining them all to a net filled with big rocks. In addition, the beginning of the film is a bit confusing and slow because the Africans’ dialogue is not translated in the early slave ship scenes and the movie doesn’t concentrate on Cinque as much as it should until the court case gets underway.

Despite these things, AMISTAD is a moving, uplifting story of heroes battling overwhelming odds to win their freedom. It contains most of Spielberg’s trademark images and themes. For example, communication across vast cultural differences leads to friendships, including that between Adams and Cinque. The same thing happens between Elliott and his alien friend in E.T. and Jim and the Japanese boy in EMPIRE OF THE SUN (arguably Spielberg’s best and most cinematic film because of its long stretches of powerful scenes with no dialogue, just John Williams’ splendid music.) Like Jim and Elliott’s alien friend, Cinque’s story becomes a journey of heroic trials that take him away from home against his will.

As he does in many of his movies, Spielberg uses everyday and natural images of light, such as a lamp or the sun, to symbolize the freedom and autonomy Cinque seeks. At one point, Cinque receives hope and comfort by speaking to his ancestors. This is an unfortunate reference to ancestor worship, but Spielberg has Adams transform this paganism into a symbolic reference to tradition when he appeals to the Founding Fathers in his Supreme Court argument. Spielberg also shows Cinque receiving hope and comfort from the New Testament when one of his fellow Africans shows him pictures of Christ’s life, death, resurrection, and ascension. This scene becomes one of the most powerful in the movie because it immediately precedes the young judge’s final verdict in the second trial.

Spielberg appears to have the most important historical facts right about the Amistad case. He does, however, neglect to show the fanaticism and extremism in the abolitionist movement. Spielberg more than makes up for this minor flaw when his movie shows that Africans themselves sold people into slavery and engaged in tribalism and civil war. AMISTAD thus contains a rare historical balance, something which many Hollywood films seldom give us.