| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

Content:

None

More Detail:

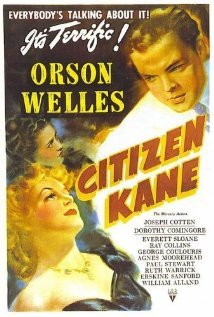

CITIZEN KANE, that quintessential American film, the one crowned the best movie ever by critics and viewers alike, returns to the screen in celebration of its fiftieth anniversary. From its fabled death-bed whispering of “Rosebud” to its staccato march-of-time like recounting of Charles Kane’s dramatic life, CITIZEN KANE delivers.

While CITIZEN KANE purportedly tells the story of newspaperman Charles Kane, it is also the thinly veiled story of media mogul, William Randolph Hearst. In addition, CITIZEN KANE turns out to be the film directorial debut of Orson Welles and his impressive genius.

As the picture opens, Charles Kane lies dying in his fabulous castle, the castle called Xanadu (shades of Khubla Khan), surrounded by his vast treasures. Then, as his eyes close in death, he utters one word: “Rosebud.”

Suddenly, the death scene is broken, and the screen becomes alive as the media rehearses Kane’s life from his humble beginnings to his great wealth and power. It tells how he became a newspaper publisher as a young man; how he aspired to political office but was defeated because of personal scandal; how he devoted himself to material acquisition; and, how he finally died.

However, the story behind the story begins when a news editor probes to discover the secret of Kane’s strange nature, and especially what he meant by “Rosebud.” Thus, a reporter is dispatched to interview those closest to Kane: his boyhood guardian, two newspaper associates, and his mistress.

They each agree that Kane was a titanic egomaniac who was consumed, in some way, by his terrifying selfishness. As to what drives Kane and whether he is villain or social parasite, never becomes clear. Even the final, poignant identification of “Rosebud” accomplishes little save to add a sentimental, human touch to Kane.

The significance of CITIZEN KANE lies in the way the tale is told: the magical camera work; the deep-focus photography; the seamless transitions from scene to scene; the abundance of imagistic details that serve to flesh out Kane’s character; and finally, the expose of Kane’s (and Hearst’s) yellow journalistic practices.

The conclusion of the matter: don’t miss this great film. In its cynicism, irony, oppressiveness, and realism, it drives home the words of Jesus: “For what shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” (Mark 8:36). It is interesting to note that throughout his career, Orson Welles peppered his profound insights with biblical quotes and references. Why he did so is a question which may not be answered until we stand before the Truth who will answer all our questions.

CITIZEN KANE shows film-making at its best with its possibility for redemptive value. An admirable achievement indeed.

While CITIZEN KANE purportedly tells the story of newspaperman Charles Kane, it is also the thinly veiled story of media mogul, William Randolph Hearst. In addition, CITIZEN KANE turns out to be the film directorial debut of Orson Welles and his impressive genius.

As the picture opens, Charles Kane lies dying in his fabulous castle, the castle called Xanadu (shades of Khubla Khan), surrounded by his vast treasures. Then, as his eyes close in death, he utters one word: “Rosebud.”

Suddenly, the death scene is broken, and the screen becomes alive as the media rehearses Kane’s life from his humble beginnings to his great wealth and power. It tells how he became a newspaper publisher as a young man; how he aspired to political office but was defeated because of personal scandal; how he devoted himself to material acquisition; and, how he finally died.

However, the story behind the story begins when a news editor probes to discover the secret of Kane’s strange nature, and especially what he meant by “Rosebud.” Thus, a reporter is dispatched to interview those closest to Kane: his boyhood guardian, two newspaper associates, and his mistress.

They each agree that Kane was a titanic egomaniac who was consumed, in some way, by his terrifying selfishness. As to what drives Kane and whether he is villain or social parasite, never becomes clear. Even the final, poignant identification of “Rosebud” accomplishes little save to add a sentimental, human touch to Kane.

The significance of CITIZEN KANE lies in the way the tale is told: the magical camera work; the deep-focus photography; the seamless transitions from scene to scene; the abundance of imagistic details that serve to flesh out Kane’s character; and finally, the expose of Kane’s (and Hearst’s) yellow journalistic practices.

The conclusion of the matter: don’t miss this great film. In its cynicism, irony, oppressiveness, and realism, it drives home the words of Jesus: “For what shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” (Mark 8:36). It is interesting to note that throughout his career, Orson Welles peppered his profound insights with biblical quotes and references. Why he did so is a question which may not be answered until we stand before the Truth who will answer all our questions.

CITIZEN KANE shows film-making at its best with its possibility for redemptive value. An admirable achievement indeed.