| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

Content:

Strong Christian worldview where main character reads Scripture & attributes athletic victory to God’s intervention, with elements of false religion; father hits son & schoolteacher hits student; no sex; and, upper male nudity & brief upper female nudity in ethnic context.

More Detail:

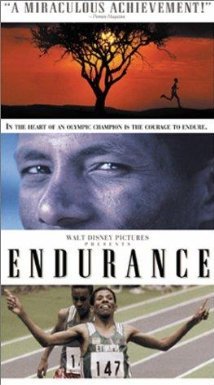

ENDURANCE was clearly the undiscovered jewel of the 1998 Telluride Film Festival in early September. Majestic, yet down-to-earth in scope, the movie depicts the stirring rise of an obscure Ethiopian dirt-farmer’s tenth son to international acclaim as the gold medal winner of the 1996 Atlanta 10,000 meter long distance run. Not since 1983’s CHARIOTS OF FIRE has an American-distributed film so closely linked the enormous human effort needed to win an international running contest with overt faith in Jesus Christ as God of the effort.

“I have to work hard, but without God, all my efforts are useless,” intones the friendly, soft-spoken Haile Gebreselassie, the movie’s hero, who looks back at the camera as it photographs him sitting on a tuft of grass. At the movie’s beginning, Haile begins his championship run in the men’s Olympic 10,000 meters final sprint around the opulent running track in Atlanta in 1996. He runs lackadaisically at first, content to stay mid-pack, then the camera flashes back to the young Haile running across dry Ethiopian highlands, schoolbook in hand. A notice informs the viewers that it is six miles to school from Haile’s farm. Against the sounds of his lungs pumping air, Haile runs and runs.

A school bell rings, boys trudge into a classroom, and the teacher begins lecturing, naming the world’s seven continents. Then, Haile enters late. Pausing in his lecture, the teacher scolds Haile and beats his hands with a wooden ruler. He tells the disconcerted schoolboy to sit down.

Later, Haile runs back home and helps his father plow the dry ground with a single-ox hand plow. As Haile works the plow, his father sits by the side of the field drinking from a glass bottle. He shouts to Haile to pay more attention to his furrows. That night, in their primitive hut, surrounded by his ten children, Haile’s father turns on a primitive radio, which announces that the UN-brokered truce has broken down and fighting has resumed in the capitol again. He turns off the radio, and Haile’s mother serves pan-baked bread to her large family from the wood-fired stove in the middle of the hut. There is no indication as to where Haile or his siblings sleep in the one-room structure.

In a subsequent scene which demonstrates how the family is economically poor, but spiritually rich, Haile reads a chapter from the Gospel of Luke, surrounded by his brothers and sisters. He reads how Jesus heals the woman with an issue of blood and raises Jairus’ dead daughter. Reinforcing the movie’s strong Christian worldview, Haile’s mother commends him to have faith.

A notice informs viewers that Mrs. Gebreselassie continues to have children, and the camera shifts to the Coptic Orthodox Church, where brightly clad priests baptize Haile’s newest brother, as his father watches. A crisis occurs, however, as Haile’s mother collapses on her way back to their hut from the water hole during the one and one-half hour’s walk from the hut. Running to her aid, Haile helps her to the hut. In what is supposed to be a private conversation but which Haile hears from the other side of the mud wall, Haile’s mother expresses grief that she won’t be able to raise her children and tells Haile’s father to take care of them. Later, four porters carry her wooden cot by hand to a primitive bus to the local hospital, but she dies. There ensues a touching and emotional funeral service, complete with keening women, who shout out the grief which the community at large experiences at Mrs. Gebrselassie’s death.

Years pass, and Haile grows up. By accident, he meets a professional running club in a field, and the coach suggests he join. He continues to run, wanting to escape the drudgery of life on the farm. His father takes him aside one day and remonstrates with him, exasperated at his lack of help around the farm, but not understanding Haile’s dream to win international running contests. He counsels Haile to go into business, like his brother. Gently, Haile explains to his father that he must pursue his dream to run. His father asks him what he can do. Haile suggests that he let him go. His father bids him farewell at the farm’s gate, and Haile leaves for Addis Ababba.

Haile goes to his brother’s house and continues training. In his first marathon, he finishes 99th. He meets a woman through the intervention of a mutual friend and invites her to share a glass of orange soda at an Ethiopian restaurant. The movie concludes with Haile’s triumphant win in the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, as he makes a final sprint to pass the redoubtable Kenyan runner who was leading the pack as his father watches from a neighbor’s television, smiling and exulting. A notice informs viewers that Haile returned to Ethiopia to a tumultuous welcome by one million countrymen.

Although it omits the crucial stage of how Haile qualified for Ethiopia’s Olympic track team once he had enrolled in the running club, ENDURANCE is a straightforward triumphant story of faith, family and persistence. With a minimum of dialogue and subtitles, the movie is a testimony to British ethnographic filmmaker Leslie Woodhead, whom producer Ed Pressman apparently hired without a script to chronicle the startling and inspiring rise of the dirt-poor Ethiopian farm boy to international prominence at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games. This is a story of a third-world runner with no connection to American Christianity who implements his faith in Jesus Christ solely from his third-world environment and wins a spectacular triumph through faith and hard work, as he is honored by his family. While its market may be limited due to the foreign languages the main characters speak and the English subtitles throughout, ENDURANCE may well requite the movie appetite of those who enjoyed CHARIOTS OF FIRE.

“I have to work hard, but without God, all my efforts are useless,” intones the friendly, soft-spoken Haile Gebreselassie, the movie’s hero, who looks back at the camera as it photographs him sitting on a tuft of grass. At the movie’s beginning, Haile begins his championship run in the men’s Olympic 10,000 meters final sprint around the opulent running track in Atlanta in 1996. He runs lackadaisically at first, content to stay mid-pack, then the camera flashes back to the young Haile running across dry Ethiopian highlands, schoolbook in hand. A notice informs the viewers that it is six miles to school from Haile’s farm. Against the sounds of his lungs pumping air, Haile runs and runs.

A school bell rings, boys trudge into a classroom, and the teacher begins lecturing, naming the world’s seven continents. Then, Haile enters late. Pausing in his lecture, the teacher scolds Haile and beats his hands with a wooden ruler. He tells the disconcerted schoolboy to sit down.

Later, Haile runs back home and helps his father plow the dry ground with a single-ox hand plow. As Haile works the plow, his father sits by the side of the field drinking from a glass bottle. He shouts to Haile to pay more attention to his furrows. That night, in their primitive hut, surrounded by his ten children, Haile’s father turns on a primitive radio, which announces that the UN-brokered truce has broken down and fighting has resumed in the capitol again. He turns off the radio, and Haile’s mother serves pan-baked bread to her large family from the wood-fired stove in the middle of the hut. There is no indication as to where Haile or his siblings sleep in the one-room structure.

In a subsequent scene which demonstrates how the family is economically poor, but spiritually rich, Haile reads a chapter from the Gospel of Luke, surrounded by his brothers and sisters. He reads how Jesus heals the woman with an issue of blood and raises Jairus’ dead daughter. Reinforcing the movie’s strong Christian worldview, Haile’s mother commends him to have faith.

A notice informs viewers that Mrs. Gebreselassie continues to have children, and the camera shifts to the Coptic Orthodox Church, where brightly clad priests baptize Haile’s newest brother, as his father watches. A crisis occurs, however, as Haile’s mother collapses on her way back to their hut from the water hole during the one and one-half hour’s walk from the hut. Running to her aid, Haile helps her to the hut. In what is supposed to be a private conversation but which Haile hears from the other side of the mud wall, Haile’s mother expresses grief that she won’t be able to raise her children and tells Haile’s father to take care of them. Later, four porters carry her wooden cot by hand to a primitive bus to the local hospital, but she dies. There ensues a touching and emotional funeral service, complete with keening women, who shout out the grief which the community at large experiences at Mrs. Gebrselassie’s death.

Years pass, and Haile grows up. By accident, he meets a professional running club in a field, and the coach suggests he join. He continues to run, wanting to escape the drudgery of life on the farm. His father takes him aside one day and remonstrates with him, exasperated at his lack of help around the farm, but not understanding Haile’s dream to win international running contests. He counsels Haile to go into business, like his brother. Gently, Haile explains to his father that he must pursue his dream to run. His father asks him what he can do. Haile suggests that he let him go. His father bids him farewell at the farm’s gate, and Haile leaves for Addis Ababba.

Haile goes to his brother’s house and continues training. In his first marathon, he finishes 99th. He meets a woman through the intervention of a mutual friend and invites her to share a glass of orange soda at an Ethiopian restaurant. The movie concludes with Haile’s triumphant win in the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, as he makes a final sprint to pass the redoubtable Kenyan runner who was leading the pack as his father watches from a neighbor’s television, smiling and exulting. A notice informs viewers that Haile returned to Ethiopia to a tumultuous welcome by one million countrymen.

Although it omits the crucial stage of how Haile qualified for Ethiopia’s Olympic track team once he had enrolled in the running club, ENDURANCE is a straightforward triumphant story of faith, family and persistence. With a minimum of dialogue and subtitles, the movie is a testimony to British ethnographic filmmaker Leslie Woodhead, whom producer Ed Pressman apparently hired without a script to chronicle the startling and inspiring rise of the dirt-poor Ethiopian farm boy to international prominence at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games. This is a story of a third-world runner with no connection to American Christianity who implements his faith in Jesus Christ solely from his third-world environment and wins a spectacular triumph through faith and hard work, as he is honored by his family. While its market may be limited due to the foreign languages the main characters speak and the English subtitles throughout, ENDURANCE may well requite the movie appetite of those who enjoyed CHARIOTS OF FIRE.

- Content:

- Content: