“Unnecessary Roughness!”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

Content:

(B, AB, H, C, LLL, VVV, S, D, RHRH, M) Mild moral worldview with positive references to God & “Our Heavenly Father” combined with immoral, humanist & Christian elements, but there is no talk of one’s ultimate salvation; 67 obscenities, 21 profanities & several vulgarities, including a couple sexual references; extreme, graphic war violence including gruesome, bloody scenes of bodies ripped open, limbs torn off, men on fire & gunshot wounds, plus many explosions; two soldiers tell bawdy stories of sexual encounters; no nudity; smoking; revisionist history of American Christians during World War II; and, miscellaneous immorality such as Americans killing three soldiers trying to surrender & German soldier lies to save his neck.

More Detail:

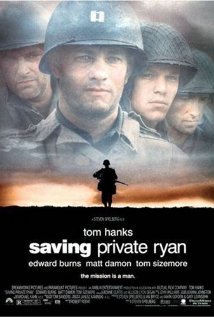

Director Steven Spielberg explores two movie genres in his new work from DreamWorks, SAVING PRIVATE RYAN. In this new movie, he mixes his penchant for making personalized historical epics, seen now in films such as EMPIRE OF THE SUN, SCHINDLER’S LIST and AMISTAD, with his long-expressed desire in making an updated, “realistic” version of the patriotic World War II war movie.

The bloody Allied Invasion of Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944 provides the epic, historical setting for the war movie that occupies most of Spielberg’s 164-minute film. And, what a bloody, horrific setting it is! Before the movie’s actual depiction of that setting, Spielberg first shows the audience the image of an American flag waving proudly but solemnly in front of the bright sun. Below the flag, an anonymous World War II veteran visits the apparent graveyards of the men who died next to him in battle. The old veteran’s family follows quietly and cautiously behind the man, who starts to cry as he slowly approaches the bleached white crosses and the few Stars of David dotting the green landscape. Suddenly, the old man stumbles and is comforted by his adult son until Spielberg’s camera zooms in on the man’s tearful eyes.

Cut to June 6, 1944, the Normandy Invasion. Spielberg’s camera focuses on one of the landing craft. The amphibious vehicle is filled with American soldiers waiting to confront the horror that was Omaha Beach. The camera lens settles on the eyes of one man in the boat, Captain John Miller, played by Oscar-winning actor Tom Hanks. Looking appropriately war-weary, Capt. Miller’s right hand shakes uncontrollably; he has obviously got a touch of shell-shock, a battle effect which is now called post-traumatic stress syndrome.

What follows this interesting opening is about 30-minutes of blood-soaked Hell. Numerous soldiers scramble in the water and on the beach while countless bullets and explosions pummel their precarious position. Many fall dead and some are graphically blown apart or shot dead. After a momentary lapse, Captain Miller slowly galvanizes his surviving men to attack the cement German pillboxes sitting atop the nearby cliffs. Helping him do this is his friend and second-in-command, Sergeant Horvath, wonderfully played by Tom Sizemore. Eventually, they take control of the situation, and the slaughter is reversed until a momentary victory is won.

Spielberg’s hand-held camera and incredible use of sound gives a documentary, you-are-there feel to the battle. He keeps his camera extremely low during this depiction of one of the most important days of the 20th Century. In an interview with a MOVIEGUIDE reporter, Spielberg said he wanted his camera to represent the many WW II combat photographers who kept very low to the ground so they could survive to record the war. Spielberg also at times uses camera techniques that give a staccato quality to the cinematic soldiers’ movements. They make parts of the battle seem like a surreal dance of death.

All of these things contribute to make this sequence from SAVING PRIVATE RYAN one of the greatest, most intense battle sequences ever filmed in a fictional movie. This sequence, however, also includes excessive, unnecessary graphic violence and excessive, unnecessary foul language. The blood, gore, obscenities, and profanities may be totally “realistic,” but they are not necessary to make the audience realize the tremendous sacrifice that the real soldiers on Omaha Beach suffered for mankind’s freedom. Other war movies have made similar, though perhaps not as intense, points about the horrors and sacrifices of war, without the same degree of violence and foul language.

After the battle, Miller, Horvath and his surviving men get a dangerous assignment to go behind enemy lines to find and retrieve one man: Private James Ryan, played by Matt Damon. The youngest of four brothers, Ryan is the last survivor, the other three having been killed in action within days of one another. As the eight-man squad pushes deeper into enemy territory, some of Miller’s men begin questioning their orders. An intense moral question begins to occupy the men as they battle a German sniper, a machine-gun nest and try to save a bridge: Why is the life of this private worth more than their own?

SAVING PRIVATE RYAN never really answers this question for the audience. Instead, it focuses on another, more important theme in the movie: the idea that the survivors of war’s horror must live morally good lives to “earn” their survival and the deaths of their buddies. The movie carries this idea to its logical conclusion: All Americans must lead morally upright, socially responsible lives to earn the freedom that their ancestors in battle paid for with their lives. If they don’t, they undermine such awful sacrifices. As one famous rock group sang about 30 years ago, “Find the cost of freedom: lay your body down.”

Spielberg has found another great moral theme for one of his movies here, and he develops the theme brilliantly. It almost, but not quite, redeems the degree of violence and foul language in SAVING PRIVATE RYAN. It fails to do so because, although the movie includes some references to God, Christianity and the Hebrew Scriptures, it includes little or no references to New Testament passages, no significant prayers to God by groups of soldiers and no real discussion of Jesus Christ other than profanities and a couple stray mentions of the Savior’s name by soldiers crossing themselves or kissing crucifixes. For a movie that claims to be “realistic” in its use of violence and foul language, this lack of specific biblical, and Christian, content is very strange indeed, especially since first-person accounts of soldiers in WW II show that these things were very important to many American soldiers in that war. Of course, the numerous accounts of World War II in bookstores and libraries and on TV are filled with works by secular historians and artists who have neglected to put such content in their work. Such historians and artists have been hard at work for years doing the same thing to the Christian roots of the rest of America’s history, including the United States Constitution and the lives of America’s Founding Fathers. Why should WW II be any different? Still, Spielberg’s failure here seems to be another example of Hollywood’s revisionist history.

Furthermore, despite fine performances from Hanks, who ranks with Gary Cooper, James Stewart and John Wayne as a quintessential American actor, and from Damon, the rest of the cast, and especially Edward Burns, their portrayals seem to lack a strong enough sense of Americana and engaging battlefield humor. These are things that great American war movies of the past, such as William Wellman’s 1946 classic BATTLEGROUND, often had.

Finally, the two big battle sequences that open and close SAVING PRIVATE RYAN just go on too long. This presents a bigger problem for the second big battle sequence because that is the one that should lead to a really exciting, moving climax. Thus, the movie’s ending seems to dilute the effect of Spielberg’s message concerning the horror of war. It also seems to dilute the impact of his revelation concerning the identity of the old veteran who appears in the opening and closing scenes of the movie.

Spielberg remains one of America’s best, most entertaining and most emotionally powerful filmmakers, however. His recent kudos in the American Film Institute’s list of top American movies are well deserved. The moral, historical and spiritual problems in SAVING PRIVATE RYAN also should not destroy his reputation as one of the most morally and spiritually uplifting, and sometimes Christian-friendly, non-Christian filmmakers working today.

- Content:

- Content: