| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

Content:

Moral worldview of preserving family through trial with inclusion of a strong Christian character & some politically correct & socialist implications of minority entitlements; 2 profanities; no violence; no sex; no nudity; alcohol use & abuse; drug use & frequent smoking; and, deceit (woman lies on resume) & stealing.

More Detail:

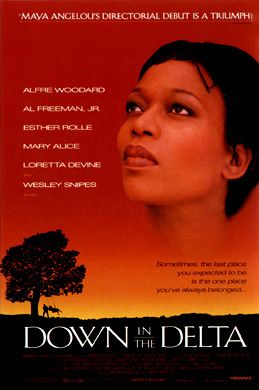

The best word to describe DOWN IN THE DELTA is “nice.” This movie, representing poet Maya Angelou’s feature film directorial debut, hasn’t got a mean bone in its body, and its intentions are laudable. Regrettably, DOWN IN THE DELTA doesn’t go very deep. It should have been a made-for-TV movie or an Oprah-endorsed “Hallmark Hall of Fame” presentation. With practice, Ms. Angelou could eventually prove formidable competition in the directorial realm. The input of a few seasoned filmmakers might temper her poetic excess. Until then, this amateurish effort can best be labeled “a good try.”

DOWN IN THE DELTA is the story of a black family that finds renewal and redemption when they move from Chicago’s inner city to the Mississippi delta. The central character is Loretta (Alfre Woodard), an alcohol-and-drug-abusing young mother of two children, Thomas and Tracy (newcomers Mpho Koaho and Kulani Hassen). Thomas is a precocious 8-year-old, while Tracy is 5 and supposedly “autistic.” No father is evident. The three live in Chicago with Loretta’s mother, Rosa Lynn (Mary Alice), who tries to hold the family together by begging her daughter to get a job and watching the children while Loretta is out partying. When her daughter botches yet another job interview, Rosa Lynn finally reaches her wits’ end. She decides to pawn her prized family heirloom, a silver candelabra she calls “Nathan” (this is explained later), so that she can send Loretta and the children to stay with her brother Earl in Mississippi.

Winningly portrayed by Al Freeman, Jr., Uncle Earl lives out in Delta Country, in what used to be “the big house” on the plantation where their family once lived in slavery. His wife, Annie (the late, incomparable Esther Rolle), and housekeeper, Zinnia (Loretta Devine), also live there. Annie wanders about in an Alzheimer’s-induced haze, yet Earl handles Annie with the utmost patience and love, as if he adored her just as much as the day they were married. Earl treats Loretta and her family with the same gentle respect and affection. He gives Loretta a job in his “Just Chicken” restaurant without hesitation. Gradually, Loretta lives up to Earl’s expectations and not only works her way up to a waitress position, but also helps manage the business.

Loretta’s children also blossom on the Mississippi farm. The autistic Tracy says her first word, and Thomas discovers nature for the first time. Earl is plainly a Christian and insists that Loretta and her children join him and Annie at church. Christianity is subtly affirmed in other ways; for example, Rosa Lynn, Thomas and the kindly Zinnia all wear crosses around their necks.

The themes of unconditional love, high moral standards, perseverance and self-reliance pervade DOWN IN THE DELTA, but somehow the film doesn’t ring true. The characters are saddled with stiff, often hokey, dialogue, and Angelou’s heavy hand is evident in their contrived gestures and expressions. In one scene, when the young Thomas’s face registers exaggerated disappointment over some news his uncle gives him, the viewer can almost hear Angelou instructing him, “OK, look sad…right…NOW!” Presumably, Angelou also asked Woodard to convey the after-effects of a drug binge by making jerky, nervous gestures that only prove distracting in their phony theatricality.

Just when it seems like the film could not get any more contrived, the movie resorts to that prosaic device plaguing every trite sitcom: the overly-explanatory phone call. When Mary Alice talks to Earl on the phone, she repeats everything he says so that the audience knows what’s happening, and even recounts old family history to give viewers background information. At this point, the movie’s artificiality simply becomes embarrassing.

Angleou also failed to research Alzheimer’s disease and autism adequately. Although Esther Rolle’s acting is stellar, Aunt Annie’s baby talk is occasionally jarring and unnecessary. Worse, Tracy’s “autism” is not remotely authentic. Autism’s symptoms are much more complex and disturbing than Tracy’s strange noises and inability to communicate. Autistic children are completely withdrawn, seldom make eye contact and often rock incessantly or have other repetitive tics. Yet, Tracy interacts with her family, responds to them with her eyes and expressions and, by the end of the movie, begins to speak expressively (most autistic kids speak in a monotone, if at all).

Compounding DOWN IN THE DELTA’s false ring, the story is also flat and unrealistic, though sweet. Loretta’s transformation from party girl to responsible mother is far too easy. She lacks the manipulative nature of true drug abusers, and she departs from her old life with hardly a backward glance. Such a transformation takes more than a mere change of environment. Furthermore, the 9-year-old Thomas seems too innocent and wise to be a product of the inner city. At a too-tender age, he sets a moral example for his own mother and is apparently unaffected by her neglect of him.

Still, this movie is refreshingly clean and good-hearted. Its PG-13 rating stems from a single scene, when Loretta is shown using drugs in a crack house. (Drug use earns an automatic PG-13, even if the movie is devoid of most other offensive material, as this film is.) Even this scene has a sitcom-like quality that, while sapping the movie of realism, won’t scare youngsters. Swear words are mild and occur only twice. The theme of triumph over slavery is tinged with a mild socialist attitude of political correctness concerning minority entitlements, but the tale is essentially a “nice” one. Even if it fails to move the audience deeply, it is a pleasant diversion from most bleak Hollywood fare.

DOWN IN THE DELTA is the story of a black family that finds renewal and redemption when they move from Chicago’s inner city to the Mississippi delta. The central character is Loretta (Alfre Woodard), an alcohol-and-drug-abusing young mother of two children, Thomas and Tracy (newcomers Mpho Koaho and Kulani Hassen). Thomas is a precocious 8-year-old, while Tracy is 5 and supposedly “autistic.” No father is evident. The three live in Chicago with Loretta’s mother, Rosa Lynn (Mary Alice), who tries to hold the family together by begging her daughter to get a job and watching the children while Loretta is out partying. When her daughter botches yet another job interview, Rosa Lynn finally reaches her wits’ end. She decides to pawn her prized family heirloom, a silver candelabra she calls “Nathan” (this is explained later), so that she can send Loretta and the children to stay with her brother Earl in Mississippi.

Winningly portrayed by Al Freeman, Jr., Uncle Earl lives out in Delta Country, in what used to be “the big house” on the plantation where their family once lived in slavery. His wife, Annie (the late, incomparable Esther Rolle), and housekeeper, Zinnia (Loretta Devine), also live there. Annie wanders about in an Alzheimer’s-induced haze, yet Earl handles Annie with the utmost patience and love, as if he adored her just as much as the day they were married. Earl treats Loretta and her family with the same gentle respect and affection. He gives Loretta a job in his “Just Chicken” restaurant without hesitation. Gradually, Loretta lives up to Earl’s expectations and not only works her way up to a waitress position, but also helps manage the business.

Loretta’s children also blossom on the Mississippi farm. The autistic Tracy says her first word, and Thomas discovers nature for the first time. Earl is plainly a Christian and insists that Loretta and her children join him and Annie at church. Christianity is subtly affirmed in other ways; for example, Rosa Lynn, Thomas and the kindly Zinnia all wear crosses around their necks.

The themes of unconditional love, high moral standards, perseverance and self-reliance pervade DOWN IN THE DELTA, but somehow the film doesn’t ring true. The characters are saddled with stiff, often hokey, dialogue, and Angelou’s heavy hand is evident in their contrived gestures and expressions. In one scene, when the young Thomas’s face registers exaggerated disappointment over some news his uncle gives him, the viewer can almost hear Angelou instructing him, “OK, look sad…right…NOW!” Presumably, Angelou also asked Woodard to convey the after-effects of a drug binge by making jerky, nervous gestures that only prove distracting in their phony theatricality.

Just when it seems like the film could not get any more contrived, the movie resorts to that prosaic device plaguing every trite sitcom: the overly-explanatory phone call. When Mary Alice talks to Earl on the phone, she repeats everything he says so that the audience knows what’s happening, and even recounts old family history to give viewers background information. At this point, the movie’s artificiality simply becomes embarrassing.

Angleou also failed to research Alzheimer’s disease and autism adequately. Although Esther Rolle’s acting is stellar, Aunt Annie’s baby talk is occasionally jarring and unnecessary. Worse, Tracy’s “autism” is not remotely authentic. Autism’s symptoms are much more complex and disturbing than Tracy’s strange noises and inability to communicate. Autistic children are completely withdrawn, seldom make eye contact and often rock incessantly or have other repetitive tics. Yet, Tracy interacts with her family, responds to them with her eyes and expressions and, by the end of the movie, begins to speak expressively (most autistic kids speak in a monotone, if at all).

Compounding DOWN IN THE DELTA’s false ring, the story is also flat and unrealistic, though sweet. Loretta’s transformation from party girl to responsible mother is far too easy. She lacks the manipulative nature of true drug abusers, and she departs from her old life with hardly a backward glance. Such a transformation takes more than a mere change of environment. Furthermore, the 9-year-old Thomas seems too innocent and wise to be a product of the inner city. At a too-tender age, he sets a moral example for his own mother and is apparently unaffected by her neglect of him.

Still, this movie is refreshingly clean and good-hearted. Its PG-13 rating stems from a single scene, when Loretta is shown using drugs in a crack house. (Drug use earns an automatic PG-13, even if the movie is devoid of most other offensive material, as this film is.) Even this scene has a sitcom-like quality that, while sapping the movie of realism, won’t scare youngsters. Swear words are mild and occur only twice. The theme of triumph over slavery is tinged with a mild socialist attitude of political correctness concerning minority entitlements, but the tale is essentially a “nice” one. Even if it fails to move the audience deeply, it is a pleasant diversion from most bleak Hollywood fare.

- Content:

- Content: