Reliance on God: How Efrem Zimbalist Jr. Replaced Anxiety with Trust

By Movieguide® Staff

Note: This story is part of our Faith in Hollywood series. For similar stories, click here.

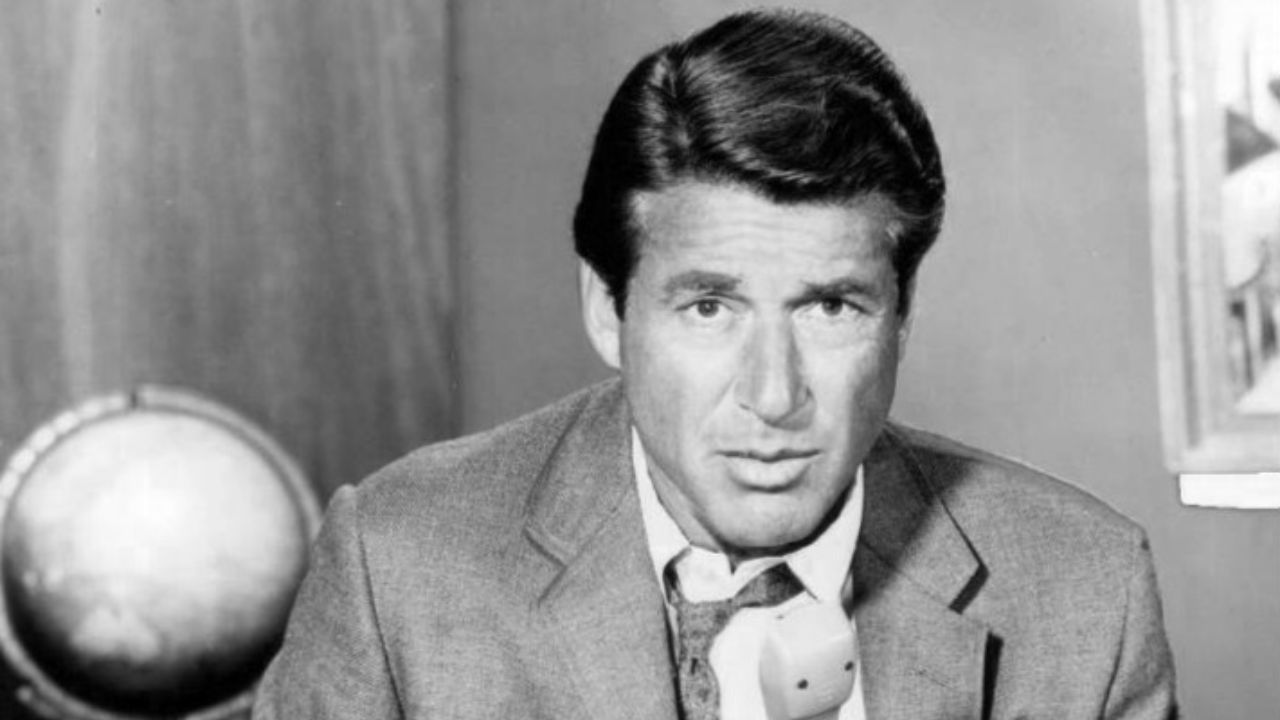

Widely known back in the day for starring in TV shows like 77 SUNSET STRIP and THE F.B.I, the late Efrem Zimbalist Jr. is also known for voicing Bruce Wayne’s butler Alfred in the 1990s DC superhero series THE NEW BATMAN ADVENTURES and SUPERMAN: THE ANIMATED SERIES.

In a 1983 article for Guideposts Magazine, Zimbalist recounted a story of personal loss and the growing pains of a deepening faith.

Owner of a fine and well-loved chocolate Packard, Zimbalist found himself a single parent with two children: Nancy, who was seven, and Efrem III, four. His wife, Emily, had passed away due to cancer, a loss that was marked by many loose ends. Not least of these unfinished adventures was some restoration work on the Packard, which wasn’t completed until after Emily’s death. Nevertheless, the car continued to hold a special place in Zimbalist’s affections.

It was the early fifties, and Zimbalist – feeling unsettled in his current state – chose to take a break from acting. Instead, he turned to another creative outlet: music. He was quite proud of his family heritage in musical talent. His mother had been a soprano known as Alma Gluck in the opera scene, his father – a lauded violinist and composer. Like his father, he put his energies into musical composition.

Before long, the actor-turned-composer was proud to have his first piece being performed for an eager public audience. Zimbalist recalls the content of his music as quite God-oriented:

I’d written a motet, a choral work sung without instrumental accompaniment. It was based on a sacred text, Psalm 150, an unusual sort of composition for me since I wasn’t all that religious. At the time, that is.

Zimbalist had put a tune to an ancient Biblical prayer that was always meant to be sung but the melody of which was lost to the ages. Even though the message was not really heartfelt at the time, he had poured out his all to make it the best he could.

He headed to Merion outside of Philadelphia to watch it be performed live. Of course, he took the old 1934 Packard.

Apart from the sheer thrill of experiencing his motet presented, Zimbalist knew that his father would also be attending the event and sharing in his big moment of pride.

While en route to Merion, Zimbalist noticed darkening clouds in the sky, but they did not affect his happy mood:

“Tah, dah, tah, tum, Praise ye the Lord … Praise Him with the timbrel and dance, dah, dab, dah, dah,” I sang, lustily, snatches of my choral work that soon would be magnified by many voices. “Oh, Prai-i-i-se Him upo-o-o-on–” POW! My left tire. My new left tire.

It certainly came as a shock. He had two spares in the car’s side-wells, but they were so old that they “couldn’t be trusted.” Zimbalist had rolled into a small town. He decided to look for a service station that might help him in his present condition – even though this was Sunday. After a call to have a tire delivered from a town 22 miles over, a local service station came to his aid, and he was soon on his merry way.

Back on the road, Zimbalist still felt the flat tire incident was a bit disconcerting. There was no reason for that new tire to blow. This, mingled with the idea of hearing his work performed before a captive audience, occupied his mind. Once again, he began to hum the tune he had written.

Just after the rain began to pour, Zimbalist heard the telltale sound of another flat. “This can’t be happening!” he said to himself.

At a stop, he jacked up the car. Then the jack busted. He ventured out to find a place he might use a phone and call for help. At the nearest farmhouse, he was declined such a favor. After further labors in the inclement weather, this second flat was fixed.

Zimbalist turned into a driver eager more than ever to reach his destination, a man short of patience. As he tried to make up for lost time, the third tire on the Packard gave out. Yet another service station visit was in order, and when he got there he gave his father a call in a disappointed tone.

He was not going to make it to the concert in time, Zimbalist told his dad. The man whose ambitions had been crushed informed his father that he should go on to the performance alone. He attempted to give his son a picture of a positive attitude, but it didn’t really work.

Back on all fours, the Packard carried Zimbalist, who was now too upset to consider the strange circumstances of his tires’ repeated failure. But his troubles were not over yet. As he vividly remembers:

And so, when the fourth one blew, I was a dangerous man. I banged shut the door of the Packard. Not even the rain could cool me off. And where was I this time? On the Henry Hudson Parkway. I could see the city, but I couldn’t get to it.

Cars whizzed past, barely missing the Packard, parked precariously on the shoulder just at the end of a curve. No one stopped to help; people only honked and yelled warnings and shook their fists.

Zimbalist was intent on finishing this trip regardless of the circumstances. Presently, an elderly man in a loud sputtering jalopy pulled up behind him and came to a halt. But the driver remained inside. The composer, still in an irritable mood, marched up to the parked vehicle and demanded to know why he had stopped since he was making no effort to get out of his jalopy.

The old face he met was a beautiful one, one whose look was one of compassion.

In a feeble voice, with frequent pauses, he explained, “I’m a little tired, and I thought I’d take a rest.”

In a bad temper, Zimbalist explained to the old man how he had a flat tire, his fourth, in fact. The jalopy-driver recommended a station about a mile and a half down the road, but the other explained how it would be impossible. The elderly man eventually offered him the jack in the back of his jalopy, handing him the keys he would need to unlock the trunk.

Muttering to himself and complaining of the man’s slow way of talking, Zimbalist trekked to the back of the vehicle, took the jack, and went over to the Packard.

But guilt stung his conscience. He should not have been so mean to this passer-by who had graciously offered guidance and assistance. Zimbalist turned around to apologize for his attitude, and to his surprise, his good Samaritan had vanished.

That noisome sputtering jalopy was nowhere to be seen, and there was no way it had just moved off without the drenched composer’s noticing. “I am losing my mind,” Zimbalist exclaimed to himself.

Later, on the train ride into Philadelphia, he sat pondering the old man, why he had come into his life at that moment, and whether he was even really there. The moment between the jalopy-driver and Zimbalist struck a chord with the actor-composer. He writes:

I never forgot that old man, and years later, when I drew closer to God, I felt–and I believe now–that that old man was sent to help me. As exasperating as he was, he gave me the help I needed. But he made me ask for it.

The whole situation – all the flat tires, his anger and anxiety, his encounter with the kind old man – brought Matthew 7:7 to Zimbalist’s mind:

Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you.

As it turned out, Zimbalist recalls that he entered the concert (a whole two hours late) “just as the choral group burst into “Praise ye the Lord … Praise Him for His mighty acts …” The 150th Psalm–my motet!”

God orchestrated something far grander than a mere motet that day. He ordained that Zimbalist would walk into that concert at the most opportune time, at the very moment a chorus broke out singing Psalm 150. The composer, though soggy from the rainy weather, sat and heard God being praised through the beauty of his music and the voices of the choir members.

Through the weakness of man, God was glorified. What the story of Efrem Zimbalist perhaps shows best is the need to put our faith in God despite the tempests of our lives. Another beautiful psalm suggests just that:

The LORD is my rock, my fortress and my deliverer; my God is my rock, in whom I take refuge. He is my shield and the horn of my salvation, my stronghold. I call to the LORD, who is worthy of praise, and I am saved from my enemies (Psalm 18:2-3).

- Content:

- Content:

– Content:

– Content: