“Soul Searching Warfare”

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

The violent battle scenes may concern older moviegoers, while younger moviegoers might chafe at the soul-searching, but at the heart of this movie is faith. Prayer runs throughout the film, and the Cross of Jesus Christ is lifted up. THE PATRIOT is thus a terrific, engrossing movie. One can only hope that this soul searching and pain will lead many to search for the God to whom Ben prays so often in this story

Content:

(CCC, LL, VVV, A, M) Christian worldview with strong moral overtones dealing with the problem of sin, redemption, freedom, family, principles, pride, & a just cause; 13 obscenities (mostly d*mn) & 1 “Oh my God” in a spiritual context; extreme violence in battlefield situations, including people’s body parts being blown off, a child being shot, several scenes of people dying, & townspeople being burned in a church by British army; no sex, but 2 lingering kisses; no nudity; alcohol use; and, plunder & the impact of the brutality of war on civilians.

More Detail:

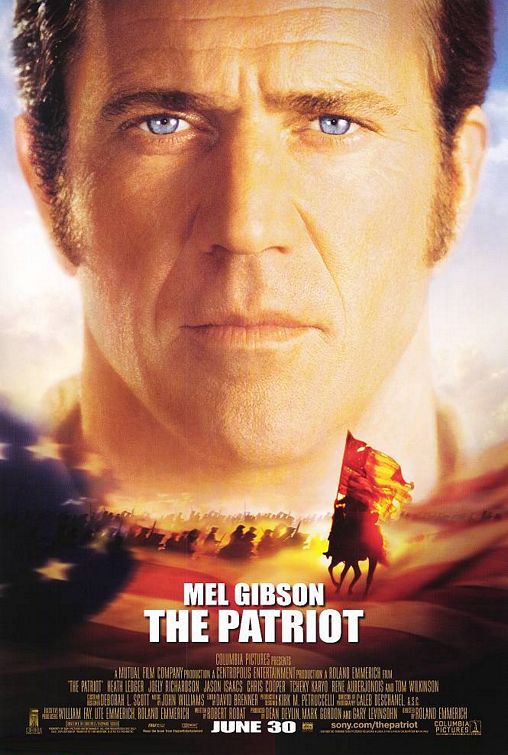

THE PATRIOT, however, is not preoccupied with the great issues of that important turning point in history, but rather about one man, Benjamin Mark, played by an incredibly introspective Mel Gibson, a man who is wrestling with his sin and the brutality of the lust for vengeance which made him a war hero in the French and Indian War. Thus, the first line in the movie says that “my sins return to visit me, and the cost is more than I can bear.” Much of the movie involves Ben’s prayers for deliverance from the passions that make him a great soldier. He wants to renounce war and take care of his seven children, given to him by his beloved wife who died just before the start of the conflict, but Providence forces him to examine himself. In this soul-searching state of mind, he tells the assembled colonials in Charleston in 1776 that family is more important than the principles of the revolution.

Regrettably, however, the war seeks him out. His older son, Gabriel, joins the Constitutional army against his better judgment. Gabriel comes home wounded, only to be captured the next day by the advancing British. The cruel British Colonel Tavington, played impeccably by Jason Isaacs, shoots Ben’s 15-year-old son, Thomas, as Gabriel is led away captive.

Thus, Ben’s fury is unleashed, and taking his two youngest boys, he goes into the woods to fight a guerilla war, slaughtering the British and rescuing Gabriel. His vengeance is so great that his youngest son fears him when he hacks up a British officer with an Indian hatchet.

When he joins up, Ben is ordered by the Constitutional army commander, his friend Colonel Harry Burwell, played well by Chris Cooper, to raise up a militia. In a fine piece of historical authenticity, a wide range of common folk are called together, including the pastor of a local church, who recognizes God’s call in this critical hour. Ben, in turn, melts down Thomas’ lead soldiers to form the bullets that he uses to kill the British.

Colonel Tavington believes that Ben is a ghost because of his ability to strike anywhere at any time with his band of men that know the country better than the back of their hands. When 18 are captured, the pastor prays in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost from deliverance from the British. At that moment, Ben rides in alone, under a white flag. Then the black militiamen clearly identify Ben, Tavington’s dreaded ghost, with the deliverance of the Holy Ghost. Ben successfully frees the 18 through a ruse that enrages Cornwallis, and causes Cornwallis to suspend the rules of war, allowing Tavington to take vengeance on the militiamen’s families. Tavington, in turn, finds the townspeople, including Gabriel’s new wife, in church. He bars the doors and burns them all in a horrendous conflagration. Rather than breaking the spirit of the militia, this act hardens their resolve, so that they surprise Cornwallis with a steadfastness that he didn’t expect from mere farmers.

Ben continues to wrestle with his sinful desire for vengeance and the worthiness of the Revolutionary cause. Eventually, he sees that he needs to stay the course, and he rejects vengeance to take up the flag.

Anyone who has a family will understand the spiritual conflict inside Benjamin Martin, but just as Benjamin‘s son Gabriel doesn’t understand Ben’s concern for his family, young moviegoers looking for action-adventure and war may be perplexed by Benjamin’s soul searching. Older moviegoers, on the other hand, will appreciate the questions being raised, but may be concerned by the violent portrayal of the bloody battle scenes.

Therefore, this spiritual movie set during a time of war may be difficult for audiences to handle. Some will want more of the political side of the Revolution to be revealed. Others will want straight war.

Instead, at the heart of this movie is faith. Though off-screen, God is one of the most prominent characters, and prayer runs throughout the film. The Cross of Jesus Christ is lifted up. And, ultimately, what the film says is that the revolution did not create a New World, it is only the spiritual revolution that comes from a living faith in a risen God that can transform a human being.

Anyone who has been around the world and seen many political systems at work would realizes that this is true. It doesn’t matter whether you live in a plantation, a Georgian colonial, or a Cape Cod, what matters is your relationship to your Creator and His work in you to create a revolution of the heart.

This extremely fine point amidst the cacophony of war may be lost on audiences. However, all that are involved in THE PATRIOT should be commended for making this point.

Written by Robert Rodat, who received a 1998 Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay for SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, THE PATRIOT is very different from Spielberg’s powerful war movie. Whereas Spielberg wanted to show how impersonal war was in SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, and many critics criticized the lack of character development, THE PATRIOT is extremely personal and focused on character. The characters are so clearly crafted that we feel their pain. One can only hope that this soul searching and pain will lead at least a few to search for the God to whom Ben prays so often in this story.

- Content:

- Content: